P

paradog

[1] Jinrui wa Suitai Shimashita, episode 7 and 8, “Yōsei-san-tachi no, Jikan Katsuyō Jutsu,” directed by Kishi Seiji, produced by AIC A.S.T.A., aired August 13 and 20, 2012. Based on the light novels by Tanaka Romeo.

[2] Aris Mousoutzanis, “Apocalyptic SF,” in The Routledge Companion to Science Fiction, ed. Mark Bould et al. (London; New York: Routledge, 2009), 457.

[3] Sophie de Mijolla-Mellor, “Alienation,” in International Dictionary of Psychoanalysis, ed. Alain de Mijolla (Detroit: Macmillan Library Reference, 2004), 43.

[4] Jacques Lacan, Ecrits: The First Complete Edition in English, trans. Bruce Fink (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2007), 525.

[5] Mark Fisher, The Weird and the Eerie (London: Repeater, 2017), 15.

[6] Fisher, 11.

[7] Fisher, 40.

[8] Mijolla-Mellor, “Alienation,” 43.

[9] Shinseiki Evangelion, 26 episodes, written and directed by Hideaki Anno and produced by Gainax, aired from October 4, 1995 to March 27, 1996, on TV Tokyo.

[10] Hiroki Azuma, “Anime or Something Like It: Neon Genesis Evangelion,” InterCommunication, 1996.

[11] Shinseiki Evangelion, episode 26, “Sekai no chūshin de ‘ai’ o sakenda kimono,” written and directed by Hideaki Anno and produced by Gainax, aired March 27, 1996, on TV Tokyo.

[12] “Toast of Tardiness,” TV Tropes, accessed August 3, 2019; “Crash-Into Hello,” TV Tropes, accessed August 3, 2019.

[13] Hiroki Azuma, Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals, trans. Jonathan E. Abel and Shion Kono (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 38.

[14] Azuma, 38.

[15]Presently, the Rebuild of Evangelion consisting of 2007’s Evangelion: 1.0 You Are (Not) Alone, 2009’s Evangelion: 2.0 You Can (Not) Advance, and 2012’s Evangelion: 3.0 You Can (Not) Redo).

[16] Derek Woods, “Scale Critique for the Anthropocene,” Minnesota Review 83, no. 1 (2014): 135.

[17] Mahō Shōjo Madoka Magika, 12 episodes, directed by Shinbo Akiyuki, written by Urobuchi Gen, and produced by Shaft, aired from January 7 to April 21, 2011, on MBS, TBS, and CBC.

[18] “Gen Urobuchi (Creator),” TV Tropes, accessed July 11, 2017.

[19] Marc Steinberg, Anime’s Media Mix: Franchising Toys and Characters in Japan (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), 84.

[20] Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2007).

[21] Free! Iwatobi Swim Club, 12 episodes, directed by Utsumi Hiroko, written by Yokotani Masahiro, and produced by Kyoto Animation, aired from July 4 to September 26, 2013, on Tokyo MX, TVA, ABC, BS11, and AT-X.

[22] Free! Eternal Summer, 13 episodes, directed by Utsumi Hiroko, written by Yokotani Masahiro, and produced by Kyoto Animation, aired from July 2 to September 24, 2014, on Tokyo MX, TVA, ABC, BS11, AT-X, NHK G Tottori.

[23] Ikari Shinji Ikusei Keikaku, developed and published by Gainax, 2004.

[24] “Neon Genesis Evangelion: Shinji Ikari Raising Project,” in Wikipedia, February 1, 2017.

[25] “Kaworu Nagisa,” in Wikipedia, January 10, 2014.

[26] Ayanami Ikusei Keikaku, developed by Gainax and BROCCOLI, published by Gainax, 2008.

[27] “Neon Genesis Evangelion: Ayanami Raising Project,” in Wikipedia, February 27, 2013.

[28] Azuma, Otaku, 48.

[29] Walter F. Isaacs, “Time and the Fourth Dimension in Painting,” College Art Journal 2, no. 1 (1942): 3.

[30] Thomas Lamarre, “Introduction,” in Mechademia 6: User Enhanced, ed. Frenchy Lunning (Minneapolis, Minn.: Univ Of Minnesota Press, 2011), ix.

[31] Rosalind E. Krauss and Yve-Alain Bois, Formless: A User’s Guide by Yve-Alain Bois (New York: Zone Books, 1997), 94.

[32] Fisher, The Weird and the Eerie, 15.

[33] Nick Compton, “Collecting Memories: Shinro Ohtake Debuts His First UK Solo Multimedia Show at Parasol Unit,” Wallpaper*, October 14, 2014, para. 4.

[34] Woods, “Scale Critique for the Anthropocene,” 135.

[35] Timothy Clark, “Telemorphosis: Theory in the Era of Climate Change, Vol. 1,” ed. Tom Cohen, Critical Climate Change, 2012, “Introduction: Scale Effects” para. 4.In the anime series Jinrui wa Suitai Shimashita (“Humanity Has Declined,” AIC, 2012), the seventh and eighth episode compose a time-traveling arc, “The Fairies’ Time Management” (Yōsei-san-tachi no, Jikan Katsuyō Jutsu),[1] recounting the story of how the series’ main character, the Heroine, came to meet the Assistant (joshu-san). The Assistant is a silent boy in a Hawaiian shirt, who helps the Heroine in her (mis)adventures with the mysterious race of creatures known as “fairies”—tiny gnome-like creature possessing advanced technology similar to magic. “The Fairies’ Time Management” begins with the Heroine being sent by her Grandfather to pick up a new helper, a feral child from an extinct ethnic minority. On her way to the village, a fairy approaches and offers her a suspicious banana. [Figure 1] After meeting with the female doctor who is in charge of the child, the Heroine learns that they have wandered off. While searching for them in a nearby forest, she comes across an unfamiliar girl who looks exactly like herself (although, at first, the Heroine does not seem to realize it). [Figure 2] As they reach a glade with a tile oven at the center, [Figure 3] the Heroine slips on a banana peel and is sent back to earlier that morning, in Groundhog Day fashion. [Figure 4] She repeats the day’s events and meets herself over and over in a spiral of déjà vu. Soon, the Heroine realizes that the fairies are manipulating time to get her clones to bake sweets—their favorite snack—resulting in a tea party packed with hundreds of the Heroine’s doppelgangers (or watashi-tachi, meaning “us”). [Figure 5] The banana is time-traveling biotechnology produced by the fairies, of which new models are presented throughout the episode. Eventually, the Heroine arrives at the village to find the central plaza crowded with dogs, [Figure 6] and finally glimpses a boy in a Hawaiian shirt: the Assistant. [Figure 7]

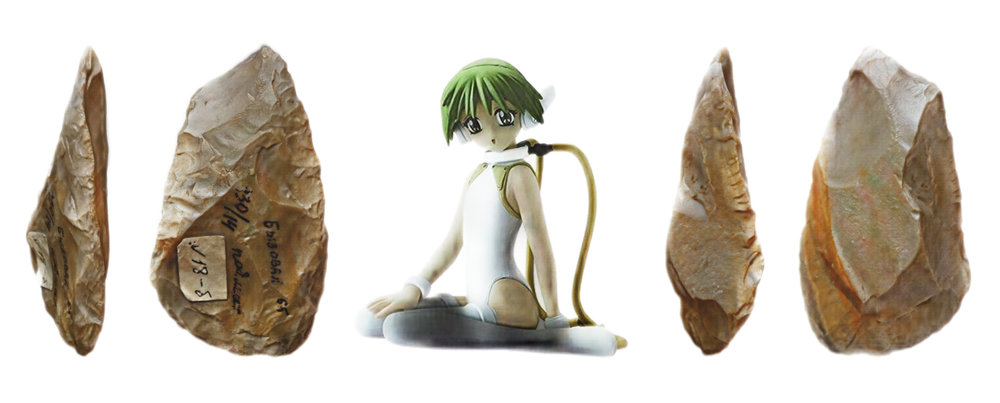

During one loop, the Heroine asks the doctor how she might identify the assistant, as they have not met before. The doctor admits that, despite having his medical data (“height, weight, blood type, heart rate, blood pressure”), she has no memory him. “He must not have a strong personality,” the Heroine suggests. “It’s worse, though. He has no real personality whatsoever,” the doctor says. “We remember others by their individual traits, right? If someone has no personality at all, nobody will be able to remember that person.” Somewhere between the fourth and fifth loop, a “bug” in the banana accidentally sends the Heroine into the faraway past. There, she meets an excitable and somewhat lecherous lad with a cowboy hat and a holster calling himself Ringo Kid, who she thinks is the Assistant but is, in fact, her Grandfather’s 13-year-old self. [Figures 8 & 9] Finally, by the sixth time loop, the Heroine meets the real Assistant, who has used her doubles’ opinions to build his personality. [Figure 10] In the end, the Assistant takes home a “time paradog”—that is, a dog created by the universe to cancel out paradoxes and restore space-time continuum by giving it the shape of a dog. Thus, “The Fairies’ Time Management” explores nonlinear parallel worlds and metafiction, in which the Assistant comes to signify a particular type of “alternativeness.”

As a blank canvas devoid of any essential individual nature, the Assistant becomes anybody’s desire, giving a Lacanian twist to the penchant for nurture over nature in alternate history fiction. On the one hand, the belief that “the exact same genetic material results in different individuals, depending on the milieu in which they live”[2] is emphasized by the doctor’s conversation with the Heroine, in which the former admits that all the medical data is not enough to define the Assistant. On the other hand, drawing on Lacan’s formula that “man’s desire is the desire of the Other,”[3] the character of the Assistant implies that everyone is already an alternate version of themselves, as we are all a product of Other’s desire and, therefore, one possible outcome out of many.

The three versions of the Assistant shown during the arc illustrate this point. The first version is the Grandfather’s desire—a macho Assistant, following his belief that “young men are meant to be buff.” The third and prevailing version originates from the tea party, a phantasmatic space of feminine desire made of the Heroine’s fairy-generated doubles. Spoken in the language of girl talk, complete with the occasional giggles, this is the Heroine’s ideal partner: “Sweet. Quiet. Gentle. Well-mannered. Soft hair. But for some reason… he wears fancy shirts. Reliable. But occasionally… bold!” Finally, the second version is Ringo Kid, named after an old Western hero from Marvel Comics. While he is technically the Heroine’s Grandfather, Ringo Kid also functions as the Assistant’s mirror image, a “what if” Assistant. He is excitable instead of gentle, loud instead of quiet, lecherous instead of well-mannered. Yet, at some point, the Heroine finds herself daydreaming that, even if she never liked that type, “maybe it isn’t so bad.” She immediately snaps out of it and reproaches herself for thinking such a thing. This incursion into in an unfrequented mental place suggests that Ringo Kid is the Heroine’s “bastard” desire, a deviant fantasy that she cannot admit even to herself, complicated by its incestuous implications.

The paradog represents the multiple (im)possibilities of human desire, “characteristic of an animal at the mercy of language.”[4] Significantly, “paradog” itself is a wordplay between “paradox” and “dog,” and the only word spoken by the Assistant during the entire show—in the voice of the famous anime voice actor Fukuyama Jun, known for his roles such as Code Geass’s Lelouch, thus reinforcing the importance of this moment within the series. Besides allowing for the wordplay, man’s best friend stands for a sense of bonhomie, the placidness of these large hounds evoking the millennia-long process of domestication and companionship between dogs and humans. [Figure 12] But also, their hollow purple eyes, and the fact that they are all exact copies of each other filling the entire town, wraps the paradogs in a sense of unfamiliarity, as if they are a “weird entity… [that] should not exist here”[5] (emphasis added), in that time and place. [Figure 13a, b] The paradog activates what Lacan calls extimité, “extimacy,” i.e., an intimate externality at our core, where the human sense of self dissolves “in the rhythms, pulsions and patternings of non-human forces,”[6] striking an aporetic in-betweenness, or vacillation, between tameness and eeriness. This eeriness—or even, the underlying horror—is present in other instances throughout the “The Fairies’ Time Management,” such as in the scene in which the Heroine barely discerns a group of fairies playing with another fairy’s severed head as if it were a ball.

As the Assistant, the paradogs are quiet and aloof, but they are connected by more than simple anachronism. Rather, as Mark Fisher puts it, “the time travel paradox plunges us into the structures that Douglas Hofstadter calls ‘strange loops’ or ‘tangled hierarchies,’ in which the orderly distinction between cause and effect is fatally disrupted.”[7] Indeed, both the Assistant and the paradog are the result of different, if connecting, forms of intimate externality. In Lacanian terms, the Assistant’s journey of self-discovery ultimately “finds its meaning in the other’s desire, not so much because the other holds the keys to the desired object, but because his first objective is to be recognized by the other.”[8] The Assistant mangles the hierarchies of causality when, having no one around to teach him words and speech, he seeks out “a sense of self, a discernible character” through time travel, taking advantage of the fairies’ technology, which carries an almost slapstick tone in its reference to the slipping banana comedy peel gag. The paradogs, in turn, serve as an outlet for the unassimilable psychosocial remainder that results from this extreme operation of longing for the Other.

Additionally, the Heroine’s own experience of time travel is one where her “self” becomes massively distributed in time through an accumulation of cycles; at the end of the episodes, there are hundreds of Heroines at the tea party. Her selves are sedimented and eroded, accumulating over each other like stratified layers that fade but shape the Heroine’s “present” memories. It is no coincidence that, at the beginning of “The Fairies’ Time Management,” the Heroine is offered a wrist sundial by her Grandfather (much to her dismay, as she preferred a mechanical watch). [Figure 14] After all, the arc is all about the Heroine’s personal “geology” and an exploration of the deep time of human desire through her interactions with the Assistant, the Grandfather, the doctor, and the fairies who play the role of catalysts. The fact that, on her way to town, the Heroine is interrupted by the Grandfather wearing a Roman helmet while riding on a chariot pulled by a horse called Deimos, further entangles these desires within the fabric of ancient civilizations and the human-technological systems that mediate our realities. [Figure 15] From “muscular” technology (chariots were used by Roman to armies to transport battle equipment, hunting, and racing) to techniques of thought and people management, like religion, as Deimos was the Greek god of terror—perhaps also alluding to fairies and their levity in messing with humans and the inviolable time-space continuum for the sake of snacks and laughs.

This kind of mise-en-abyme is present in classic Japanese animations such as Shin Seiki Evangelion (Neon Genesis Evangelion, 1995-96)[9] or Miyazaki Hayao’s Howl no Ugoku Shiro (Howl’s Moving Castle, 2004). In Evangelion’s case, as with Jinrui, it also relates to the broader theme of the kyara and its propensity for derivation, distribution, and “viscosity.” Evangelion is originally a twenty-six-episode anime series produced by studio Gainax and written and directed by Anno Hideaki. Although, technically, Evangelion fits into the mecha anime category, i.e., a type of anime about giant anthropomorphic robot weapons and the pilots who ride them (pioneered by Nagai Go’s Mazinger Z and Tomino Yoshiyuki’s Mobile Suit Gundam in the 1970s), it defies categorization, being credited with reviving the 1990s anime industry.[10] The story’s main characters are the protagonist Ikari Shinji, a boy pilot, two iconic sentō bishōjo (“beautiful fighting girls”), taciturn Ayanami Rei and hot-headed Soryu Asuka Langley, and their military strategist, a young adult woman named Katsuragi Misato. They belong to a mysterious organization called NERV and struggle to defend the city of Tokyo 3 from the relentless attacks of polymorphous creatures called Angels, about which they know very little. One of Evangelion’s most memorable moments is the last two episodes, representing what is called, within the series, the Human Instrumentality Project.

In episode 26, titled “Sekai no chuushin de ‘ai’ o sakenda kemono,”[11] the series’ narrative fabric begins to fall apart. Indeed, the title, translated as “The Beast that Shouted ‘I’ at the Heart of the World,” is a pun on the The Beast that Shouted Love at the Heart of the World, a 1968 sci-fi short story by Harlan Ellison (in Japanese, the word for “love,” “ai,” 愛, is pronounced the same as the English word “I”), famous for its experimental, non-sequential narrative. In the episode, the viewer is presented with a short anime within the anime. The episode recreates a parallel world in which Shinji is just an average high school student who lives with his parents, Asuka is his best childhood friend, Rei is a lively transfer student, and Misato is their teacher. This completely different story is full of trite anime tropes, including the Toast of Tardiness (Rei runs late to school while) and a Crash Into Hello (Rei and Shinji bump into each other).[12] [Figure 17] Confronted with this alternate version of himself and others, Shinji eventually remarks: “I see, this is another possibility. Another possible world. This Self is the same way, it’s not my true Self. I can be any way I wish to be,” coming to terms with the dessentialization of his identity, and its embeddedness in situated (i.e., time and space-specific) worlds. [Figure 18]

While this moment corresponds to Shinji’s understanding that the reality that he inhabits is just one among many possibilities, there is a meta-level to his epiphany. According to philosopher Azuma Hiroki, “Hideaki Anno (the director of Evangelion) anticipated the appearance of derivative fan works in the Comiket, one of the world’s largest comic conventions, mostly dedicated to amateur manga parodies of commercial shows. As such, from the beginning, Anno set up various gimmicks within the original to promote those products.”[13] Indeed, according to Azuma, many “high school alternate universe” (or AU, for short) fan works, in which a series’ cast is transplanted into a different world where they are high school students, were already circulating by the time of this episode’s original broadcast in March of 1996.[14] Therefore, this high school AU within Evangelion is not only a self-conscious parody but a reaching out from the creator towards the Others’ (the fans’) desire—an acceptance that derivation, even in its banalizing dimension of original authorial works, is the inevitable fate of any original within the postmodern logic of otaku culture. More recently, Anno himself has been participating in this continuous process of derivation with an ongoing movie tetralogy called Rebuild of Evangelion,[15] in which he takes the building blocks of the original series, its kyara and settings, and remixes them into a whole different shape. [Figure 19] Arguably, every time a fan creates a derivative work (fan fiction, fan art, fan comics, etc.), a paradog emerges to make up for the “disjunctures and incommensurable differences among [the] scales”[16] and hierarchies of creative and affective networks.

This self-conscious play with the kyara’s “viscosity” (i.e., a character’s capacity to bind together a high number of variations and related works across different media) has become a popular device in animanga shows since Evangelion, used in both serious and lighthearted ways. For instance, in Mahō Shōjo Madoka Magika (Puella Magi Madoka Magica, Shaft, 2011),[17] a ground-breaking magical girl anime that put a horror and psychological twist on the genre, the character Akemi Homura travels relentlessly into the past, remaking the same events time after time to avoid the death of the protagonist, Kaname Madoka. [Figure 20] At the end of the series, the viewer is shown glimpses of the multiple timelines in which Homura fails to save Madoka, with various bad endings. In a similar vein, the series opening credits feature Madoka in a plethora of outfits and comical situations that never actually take place in the show, whose tone is dark and deconstructive. [Video 1] Moreover, after each failure, Homura returns to a “saved” point in time, as if she was in a videogame. It is significant to note that Madoka’s writer, Urobuchi Gen, is a celebrated author of visual novels with tragic settings and bold plot twists.[18]

Eventually, the snowballing synergy of these entangled time travel loops, of which Madoka is the affective core, modifies not only Homura’s kyara, who shifts from a shy “shrinking violet” to a full-fledged tsundere character with fierce fighting skills, but also Madoka herself, prompting her transformation into an über-magical girl at the climax of the series. As media theorist Marc Steinberg puts it, when it comes to the kyara, “each material incarnation… effectively transforms the abstract character image, and this tingeing or layering of each of the characters’ incarnation compounds or snowballs.”[19] These time and material entanglements are represented visually in the show by evocative shots of Homura and Madoka hanging from several threads, while the wheels of a clock turn behind them (moreover, their position, similar to Christ on the cross, echoes the Christian imagery of messianic sacrifice). [Figure 21a, b] Thus, while in Jinrui, the Assistant is shaped by the Heroine’s desire, Madoka becomes the product of her “assistant” Homura, a role reversal that subverts the audience’s expectation of the protagonist as the “chosen one” who autonomously exerts their messianic force on the world and saves the day. Nevertheless, all these shows recognize and highlight the entanglement of characters and their intra-actions[20] with each other, their worlds, and their audiences, questioning the deterministic assumptions that separate the canon narrative from its alternatives.

On a more lighthearted note, another anime, Free! Iwatobi Swim Club (Kyoto Animation, 2013),[21] a sports anime about a group of high school boys in a swimming club, and its sequel Free! Eternal Summer (Kyoto Animation, 2014),[22] which became immensely popular among female anime fans, also plays with these mechanics. Free!’s original series and sequel feature two ending credits that became the target of endless Internet memes, due to their blatant use of “alternate universe” to stimulate the fan’s imagination. The first ending is an Arabian AU in which the swim club boys appear dressed in sexy Arab costumes; the second is an AU where they have alternative professions—chef, policeman, fireman, astronaut—showing snippets of their daily lives and interactions. [Video 2] In both cases, it did not take long for fan art, fan fiction and other types of fan labor like cosplay, to emerge based on the character variations and alternative worlds featured in Free!’s endings.

In Evangelion’s case, the original television series has spawned an abnormal plethora of manga, anime, novels, and videogames that differ from the original television series sometimes subtly, sometimes radically. These introduce semi-alternative or entirely alternative universes, exploring non-canonical romantic relations between characters, telling previously unseen side stories, or, in Rebuild of Evangelion, re-imagining the conflicts from the original anime. Some spin-offs change the series’ original sci-fi genre into a high school romantic comedy, like Angelic Days (2003-2005); or “whodunit” murder mysteries, like Shinji Ikari’s Detective Diary (2010); [Figure 22] or cutesy-styled parodies like Petit Eva: Evangelion@School (2007-2009). In the videogame Ikari Shinji Ikusei Keikaku (Shinji Ikari Raising Project, 2004),[23] the player “raises” the protagonist, Shinji, by deciding on his life options such as career and romantic partner.[24] Shinji, whose “profession” in the original anime series is to pilot a giant anthropomorphic robot, can thus become a basketball player, a university student, a cello player, a teacher, an artist, a novelist, and so on. He can also pursue romantic relationships with the series main girls, such as Rei, Asuka or Misato, and even a gay “boys’love” relationship with the enigmatic “beautiful boy” (bishōnen) Nagisa Kaworu (who, despite his short screen time in the original series, became one of the most popular 1990s male anime characters, and features extensively in merchandise and spinoffs.)[25] In another game, Ayanami Ikusei Keikaku (Ayanami Raising Project, 2001),[26] the player looks after Rei, balancing her weekly schedule of education, work, and leisure, in a mix of digital pet and dating simulation gameplay.[27] In such products, the continuity in terms of content with the original series is extremely weak. [Figure 23a, b]

Nevertheless, both the original and the “related goods” are avidly sought‑after by fans. More than the work’s authorship or message, then, kyara have become the binding glue of the many ramifications of the Evangelion franchise, whose outputs are often not contiguous among themselves, changing radically in terms of plotline, characters’ personalities, and even art style and general aesthetics.[28] As such, while time and space are engrained within any artwork’s experience (as artist and writer Walter F. Isaacs’s words, “Life experience is a ‘space-time’ experience, and so is that of every work of fine art”),[29] the above works problematize in a direct manner the narrative deep time and the massive distribution of “commodity-events.”[30] The medium of painting, however, is equally suitable for perceptualizing these paradogs, especially when the superposition and sedimentation of layers are made on all fours, i.e., “against the axis of the human body,”[31] of which Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings are the ultimate example. [Figure 24] Isa Genzken’s (b. 1948) wall-based assemblages are another such instance, suggesting a time-space against the human axis. Like Pollock’s canvases, Genzken’s paintings aggregate pictures from books and magazine together with unorthodox materials like adhesive tape, lacquer and spray paint, in a gesture whose radical “sensation of wrongness”[32] shocks the viewer’s sensorium. [Figure 25a, b] In forcing us to make sense of a realm beyond everydayness, Genzken’s works bring into view the vitality of these supposedly non-painterly materials of mass-cultural, commodified origin.

In Japanese art, Ohtake Shiro’s (b. 1955) works, such as his scrapbooks, aptly fit into this tradition. Influenced by Pop Art, Ohtake made his first scrapbook in 1977, during a trip to London, “filling it with his own sketches and photographs but also bus tickets and torn scraps of packaging” in an “archaeology of another consumer culture.”[33] In these scrapbooks, composed of up to eight hundred pages painted and glued with found objects, newspaper clippings, and other mementos, the picture gains a sculptural breath, raising from its flat confines into a tridimensional arena where it unfolds almost like a biological organism. [Figure 26a, b] Aggregated in this way, the pop-cultural fragments in Ohtake’s scrapbooks reveal not only the prolonged span of the artistic gesture over the scope of nearly 40 years, but the deep mediatic time of their genealogies—and geographies, and geologies—impressed on the pages. Tellingly, the scrapbooks are “measured” not only by the number of pages but also by their weight, negating the lightness, flatness, and thinness associated with drawing and paper, and linking them with natural phenomena like gravity involved in physical objects. The paradog is an appropriate framework for digging into these works, as the “scale disjuncture”[34] of their Pop Art imagery add an element of humor, sometimes even cuteness, to their weirdness. For instance, Ohtake’s scrapbooks often reference the infantile, featuring children’s cartoon characters or a myriad of doll plastic eyes. In one case, an amalgamation of toy eyeballs seemingly rises from the deep to the surface of the book’s cover, like a makeshift Cthulhu, unsettling and silly in equal measure. [Figure 27] In the end, these various instances of art and pop culture suggest that time-space paradoxes and alternative universes require “non-cartographic concepts of scale [that] are not a smooth zooming in and out but involve jumps and discontinuities with sometimes incalculable scale effects.”[35] Such residue, the “incalculable effect” of our ever-shifting becoming, is embodied by the paradog as a metaphor for the unassimilable, unmeaning excess on which both life and art fundamentally thrive.

See in CUTENCYCLOPEDIA – Fairies.

See in PORTFOLIO – Obscure Alternatives & Spookytongue.

REFERENCES in Paradog.

MAJOR SPOILERS!

Jinrui wa suita shimashita (anime)Neon Genesis Evangelion (anime)Puella Magi Madoka Magica (anime)

Figure 1 A fairy approaches the Heroine with a banana. Source: Jinrui wa Suitai Shimashita, episode 7, “Yōsei-san-tachi no, Jikan Katsuyō Jutsu,” directed by Kishi Seiji, produced by AIC A.S.T.A., aired August 13, 2012. Based on the light novels by Tanaka Romeo.

Figure 2 The Heroine meets her doppelgangers. Source: Jinrui wa Suitai Shimashita, episode 7, “Yōsei-san-tachi no, Jikan Katsuyō Jutsu.”

Figure 3 The glade with the tile oven. Source: Jinrui wa Suitai Shimashita, episode 7, “Yōsei-san-tachi no, Jikan Katsuyō Jutsu.”

Figure 4 The slipping banana.

Figure 5 The slipping banana. Source: Jinrui wa Suitai Shimashita, episode 7, “Yōsei-san-tachi no, Jikan Katsuyō Jutsu.”

Figure 6 The dog-filled town plaza. Source: Jinrui wa Suitai Shimashita, episode 7, “Yōsei-san-tachi no, Jikan Katsuyō Jutsu.”

Figure 7 The Heroine glimpses the Assistant. Source: Jinrui wa Suitai Shimashita, episode 7, “Yōsei-san-tachi no, Jikan Katsuyō Jutsu.”

Figure 8 The Heroine travels to the past and meets Ringo Kid. Source: Source: Jinrui wa Suitai Shimashita, episode 8, “Yōsei-san-tachi no, Jikan Katsuyō Jutsu,” directed by Kishi Seiji, produced by AIC A.S.T.A., aired August 20, 2012.

Figure 9 Ringo Kid surprises the Heroine with a kiss. Source: Jinrui wa Suitai Shimashita, episode 8, “Yōsei-san-tachi no, Jikan Katsuyō Jutsu.”

Figure 10 The Heroine and the Assistant meet at last. Source: Jinrui wa Suitai Shimashita, episode 8, “Yōsei-san-tachi no, Jikan Katsuyō Jutsu.”

Figure 11 The time paradox in the shape of a dog – a “paradog.” Source: Jinrui wa Suitai Shimashita, episode 8, “Yōsei-san-tachi no, Jikan Katsuyō Jutsu.”

Figure 12 The paradog’s placid look. Source: Jinrui wa Suitai Shimashita, episode 8, “Yōsei-san-tachi no, Jikan Katsuyō Jutsu.”

Fugure 13a A closer look reveals the paradog’s somewhat threatening look. Jinrui wa Suitai Shimashita, episode 7, “Yōsei-san-tachi no, Jikan Katsuyō Jutsu.”

Figure 13b A closer look reveals the paradog’s somewhat threatening look. Jinrui wa Suitai Shimashita, episode 7, “Yōsei-san-tachi no, Jikan Katsuyō Jutsu.”

Figure 14 The Heroine’s sundial. Jinrui wa Suitai Shimashita, episode 7, “Yōsei-san-tachi no, Jikan Katsuyō Jutsu.”

Figure 15 The Heroine’s Grandfather in Roman apparel and the horse Deimos. Jinrui wa Suitai Shimashita, episode 7, “Yōsei-san-tachi no, Jikan Katsuyō Jutsu.”

Figure 16 Shinseiki Evangelion (Neon Genesis Evangelion), originally run from October 4, 1995, to March 27, 1996. At the center is Ikari Shinji, on the left and right Ayanami Rei and Soryu Asuka Langley, and above is Nagisa Kaworu. Source.

Figure 17 An alternative reality in which the taciturn Rei is a lively high school student. Source: Shinseiki Evangelion, episode 26, “Sekai no chūshin de ‘ai’ o sakenda kimono,” written and directed by Hideaki Anno and produced by Gainax, aired March 27, 1996, on TV Tokyo. (GIF via).

Figure 18 Shinji coming to terms with the dessentialization of his identity, and its embeddedness in situated worlds. Source: Shinseiki Evangelion, episode 26, “Sekai no chūshin de ‘ai’ o sakenda kemono.”

Figure 19 Poster of the 2012 film Evangelion: 3.0 You Can (Not) Redo, the third of four films released in the Rebuild of Evangelion tetralogy. Source.

Figure 20 Akemi Homura, the time traveler in Puella Magi Madoka Magica. Source: Mahō Shōjo Madoka Magika, 12 episodes, directed by Shinbo Akiyuki, written by Urobuchi Gen, and produced by Shaft, aired from January 7 to April 21, 2011, on MBS, TBS, and CBC (GIF via).

Video 1 Opening credits of the 2011 anime Puella Magi Madoka Magica. At 0:23, we are shown several vignettes of alternative realities that never get to happen in the show. Source.

Figure 21a Homura’s entanglement in time. Source: Mahō Shōjo Madoka Magika (GIF via).

Figure 21b Madoka as the focal point of Homura’s (affective) time dimensions. Source: Mahō Shōjo Madoka Magika (GIF via).

Video 2 Ending credits of Free! Eternal Summer, showing the cast of high school students living different lives and professions. Source: Free! Eternal Summer, 13 episodes, directed by Utsumi Hiroko, written by Yokotani Masahiro, and produced by Kyoto Animation, aired from July 2 to September 24, 2014, on Tokyo MX, TVA, ABC, BS11, AT-X, NHK G Tottori (via).

Figure 22 Book cover of Yoshimura Takumi’s The Shinji Ikari Detective Diary, published in English by Dark Horse, 2013. Source.

Figure 23a Screengrab from the Kaworu route in the videogame Shin Seiki Evangelion: Ikari Shinji Ikusei Keikaku (Shinji Ikari Raising Project), developed and published by Gainax, 2004. Source.

Figure 23b Screengrab from the videogame Shin Seiki Evangelion: Ayanami Ikusei Keikaku (Ayanami Raising Project), developed by Gainax and BROCCOLI, published by Gainax, 2001. Source.

Figure 24 Jackson Pollock’s Autumn Rhythm (Number 30), 1950. Source.

Figure 25a Isa Genzken, Kinder Filmen I, 2005. Mirror, metal, adhesive tape, magazine and book pages, stamps acrylic, lacquer, spray paint, 280 x 100 cm each panel. Source.

Figure 25b Isa Genzken, Untitled, 2016. Photographs, glitter, paper tape, metallic tape, plastic tape, acrylic paint, bank coin, card, paper and plastic foil, 99 x 95 cm. Source.

Figure 26a Ohtake Shinro, Scrapbook #66, 2010 – 2012. Mixed media artist book, 72 x 96 x 129 cm 27.2 kg, 830 pages. Source.

Figure 26b Detail from a scrapbook by Ohtake Shinro. Source.

Figure 27 Cthulhu-ish book cover of scrapbook by Ohtake Shinro. Source.

ABSOLUTE BOYFRIEND ; (BETAMALE) ; BLINGEE ; CGDCT ; CREEPYPASTA ; DARK WEB BAKE SALE ; END, THE ; FAIRIES ; FLOATING DAKIMAKURA ; GAIJIN MANGAKA ; GAKKOGURASHI ; GESAMPTCUTEWERK; GRIMES, NOKIA, YOLANDI ; HAMSTER ; HIRO UNIVERSE ; IKA-TAKO VIRUS ; IT GIRL ; METAMORPHOSIS ; NOTHING THAT’S REALLY THERE; PARADOG ; PASTEL TURN ; POISON GIRLS ; POPPY ; RED TOAD TUMBLR POST ; SHE’S NOT YOUR WAIFU, SHE’S AN ELDRITCH ABOMINATION ; ZOMBIEFLAT