Anime was a mistake. It’s nothing but trash.

— Hayao Miyazaki (troll quote)

I am interested in the Japanization of Western youth in the twenty-first century. As a millennial, I grew up with manga, anime, and Japanese video games; to this day, I obsess over them, even after years of formal education in fine arts. I am what they call weeaboo trash, an Internet slur for the annoying Japan-obsessed Westerner—the “wannabe Japanese.” A neurosis of late-capitalist globalization, the weeaboo condition challenges the pacifying discourses of hybridism and internationalism that often surround the spread of cultural soft powers, be it in the physical or digital world.

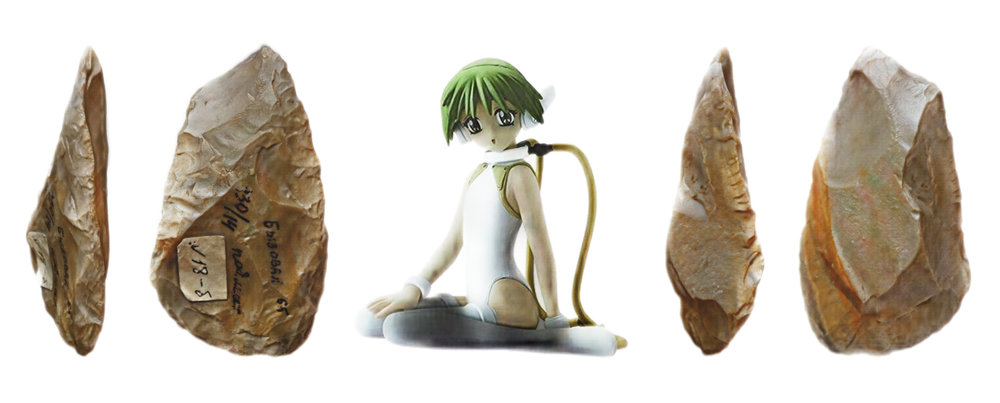

In my work, I exploit a loophole between the colorful, easy-to-read and overdetermined (if lost in translation) cuteness of much Japanese pop culture and its shadow opposite: the meaning-resistant, raw pictorial and affective materials yet to be processed into a proper commodity form. Thus, by pitting big-eyed fantasy characters, kawaii mascots, emoji, aidoru, and so on against the abstract, chancical, automatic or nonsensical operations associated in art history with the Western avant-garde, I aim to produce a double effect. On the one hand, the “dumbing down” of formal purity by (J-) subcultural styles, unsuited for high modernist aesthetics. On the other, highlighting the intimate alienation at the core of the weeaboo’s emotional attachment to products “made in Japan.” I often employ Japanese brands, materials, and software to bring out and expose these fetishistic drives.

Collage and provisionality play a crucial role in the layering of visual, narrative, and conceptual elements to create immersive, multifaceted experiences for the audience; for example, in comics like Violent Delights (kuš!, 2020), Spookytongue (Ediciones Valientes, 2017), “Trance Dream Techno” (in š! #25 Gaijin Mangaka, 2016) or Muji Life (Clube do Inferno, 2015). This also applies to my work across media besides comics, like painting, photography, video, installation, and essays—from the wall accumulations of small drawings and paintings which I have created over the last decade to my non-linear Ph.D. dissertation, CUTENCYCLOPEDIA, focusing on the links between cuteness and abjection and hosted online, on my website. Color and texture work to reinforce the primal, sensual side of my images, tending towards the lurid or even shocking to the senses.

In 2020, I started using a pen plotter to render digital paintings on paper using archival ink pens. These pieces inhabit a liminal materiality between the analog and the digital, enacting a conflict between the clean high-tech processes that go against the human (and artist’s) touch, on the one hand, and, on the other, “low” matters ranging from the sparkling cuteness of Blingee GIFs and anime fantasies to discarded painted materials collected from my studio, garbage or graffiti, which are photographed and inserted into the plotted montages.

My struggles as a weeaboo and an artist between Western and Japanese, subculture and art, will resonate with those who are in the same boat as me. However, I believe that the experience of the “intimate as Other” is universal. Pictures draw us to behold and snuggle into them, only to wield their subsemiotic powers counter to interpretation, whose signal is distorted by environmental noises—pointing towards a broader boundary-violating impulse towards human identity and matters. Performing this “extimacy” (Lacan) in the realm of art can help us gain a better grasp, and productively engage with, the many cultural-ecological disasters of our time.

Recently, I began to include new materialist and Anthropocene perspectives in my theoretical research and art, informed by the work developed under the Japanized banner while experimenting beyond it, with themes related to history, science, and technology. My comic Asbestos in Ambler (Anthropocene Curriculum, 2017) and the graphic novel Einstein, Eddington and the Eclipse: Travel Impressions (Chili Com Carne, 2019) exemplify this kind of output.