M

Metamorphosis

[1] Patricia Yaeger, “Editor’s Column: The Death of Nature and the Apotheosis of Trash; or, Rubbish Ecology,” PMLA 123, no. 2 (March 1, 2008): 321.

[2] Mr. Metamorphosis: Give Me Your Wings, LM Artist Video Series (New York: Ra/oR Media, 2012).

[3] Kris Scheifele, “The Financial Crisis and Other Natural Disasters, A Tour in Three Parts,” Hyperallergic (blog), September 20, 2012.

[4] The video is available at Lehmann Maupin’s website here.

[5] Mr, I eat curry one day and fish another, interview by Melissa Chiu, Book section of “Mr.,” 2011, 4; Hannah Stamler, “Murakami Protégé Mr. Invites You into the Dark Depths of Neo-Pop,” The Creators Project, February 23, 2015; “Mr. - Metamorphosis: Give Me Your Wings” (Lehmann Maupin, September 13, 2012).

[6] Artists associated with he Mono-ha movement included Nobuo Sekine, Lee Ufan, Katsuro Yoshida, Susumu Koshimizu, Koji Enokura, Kishio Suga, Noboru Takayama, and Katsuhiko Narita Ashley Rawling, “An Introduction to ‘Mono-Ha,’” September 8, 2007, para. 1-3.

[7] “Mr. - Metamorphosis: Give Me Your Wings.”

[8] Stamler, “Murakami Protégé Mr. Invites You into the Dark Depths of Neo-Pop.”

[9] “Mr. - Sunset in My Heart” (Lehmann Maupin, June 23, 2016).

[10] “Mr. - Sunset in My Heart.”

[11] “Mr. - Sunset in My Heart.”

[12] Michael Wilson, “Mr., ‘Sunset in My Heart,’” Time Out New York, May 18, 2016.

[13] Wilson.

[14] Harry Harootunian, “Japan’s Long Postwar: The Trick of Memory and the Ruse of History,” in Japan After Japan: Social and Cultural Life from the Recessionary 1990s to the Present, ed. Tomiko Yoda and Harry Harootunian (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2006), 98–121.

[15] Scheifele, “The Financial Crisis and Other Natural Disasters, A Tour in Three Parts.”

[16] Scheifele.

[17] Marilyn Ivy, Discourses of the Vanishing: Modernity, Phantasm, Japan, 1 edition (Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 1995), 7.

[18] Wester Wagenaar, “Wacky Japan: : A New Face of Orientalism,” Asia in Focus: A Nordic Journal on Asia by Early Career Researchers, no. 3 (2016): 46–54.

[19] Masakatsu Iwamoto and Galerie Perrotin, “People Misunderstand Me and the Contents of My Paintings. They Just Think They Are Nostalgic, Cute, and Look like Japanese Anime. That May Be True, but Really, I Paint Daily in Order to Escape the Devil That Haunts My Soul. The Said Devil Also Resides in My Blood, and I Cannot Escape from It No Matter How I Wish. So I Paint in Resignation,” Perrotin, 2018.

[20] Yaeger, “Editor’s Column.”

[21] “Manga Café,” Only in Japan, accessed September 27, 2018.

[22] “Net Cafe Refugee,” in Wikipedia, May 23, 2018.

[23] Installation Art (London: Tate, 2010), 14.

[24] The Man Who Flew Into Space from his Apartment was made in Moscow in 1985, but first shown to the public in New York in 1988, after Kabakov left the Soviet Union.

[25] Ilya Kabakov: The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment (London: Afterall Books, 2006), 1.

[26] The Seeds of Time (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996), xii.

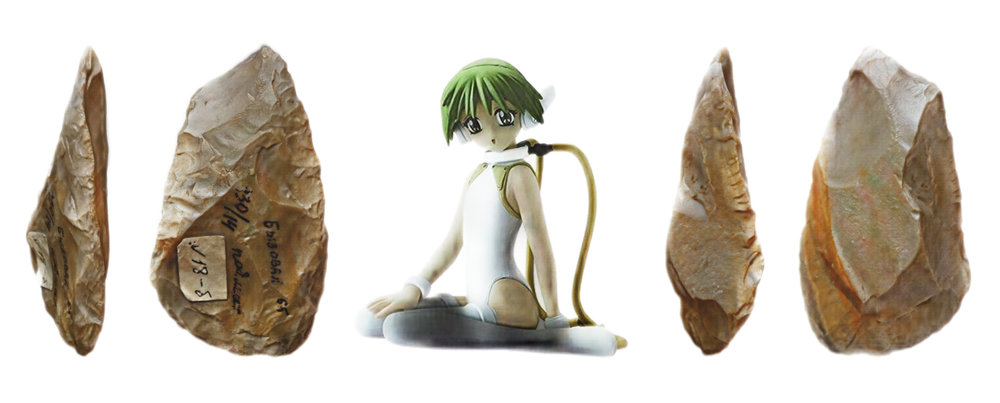

[27] Patrick W. Galbraith, “Introduction: Falling In Love With Japanese Characters,” in The Moe Manifesto: An Insider’s Look at the Worlds of Manga, Anime, and Gaming (North Clarendon, VT: Tuttle Publishing, 2014), 8.September 2012, New York: a colossal centerpiece stands at the center of Lehmann Maupin, a gallery located in the Chelsea neighborhood. [Figure 1a, b] The piece calls to mind what scholar Patricia Yaeger once called an “apotheosis of trash,”[1] consisting of a considerable collection of plastic bags, televisions, computer screens, Christmas lights, cardboard boxes, packages, bottles, discarded clothes, blankets, towels, comic books, magazines, hangers, fans, and so on. The garbage pile seems to form the shape of a caterpillar or a cocoon, loosely. Or of a whale, washed up on the beach. In turn, this garbage caterpillar is surrounded by paintings of anime girls, drawings, photographs of everyday objects—food, cityscapes, selfies—miscellaneous furniture, and graffiti painted directly on the gallery’s walls. [Figure 2] The overall impression is not that of a typical “white cube,” but a messier space that both captures the viewer’s attention and threatens to fall and crush them under the mountain of debris.

This memorable scene is from Metamorphosis; Give Me Your Wings (September 13–October 20, 2012), an exhibition by the Japanese artist Iwamoto Masakatsu (b. 1969), better known by the pseudonym Mr., as well as by his association with Murakami Takashi’s Kaikai Kiki collective. According to Mr., the garbage caterpillar symbolizes the death and rebirth of Japan in a “process of metamorphosis that never seems to be complete.”[2] In this sense, it is both scatological and eschatological, alluding to Japan’s many disintegrations: first vaporized by the atomic bomb, then again reduced to floating debris by the earthquake and tsunami of 2011, joining the gyres of marine pollution such as the Great Pacific garbage patch. [Figure 3] As Kris Scheifele puts it, in Metamorphosis, the “water and human hubris play some role in creating the chaos; our dangerous love affair with stuff—and lots of it—enhances the devastation.”[3] Metamorphosis’s horror vacui, i.e., its fear of the empty, means that there are all kinds of stuff propped up on the walls and scattered around the floor. [Figure 4a, b] Cardboard and plastic boxes, clothes, and crumpled fabrics, eating and drinking utensils, balloons, mats, furniture (shelves, cabinets, chairs, benches, small tables, screens), tangled power cables, endless stacks of newspapers, books, and manga magazines. At one point, there is an enormous photograph of a plate with remnants of sauce and food. [Figure 5] There are small sketches everywhere. [Figure 6] Huge graffiti faces of animanga characters decorate the walls, along with hiragana and katakana tags mixed with the Roman alphabet, for example, the painted word “Ikebu く ろ,” referring to the Tokyo district known as a hotspot of otaku culture.

On the gallery’s walls, there is a series of five paintings featuring Mr.’s trademark moé girls, their wind-tossed hair and skirts rendered in minute detail. [Figure 7a, b] The characters’ beauty in the wind is reminiscent of Hokusai’s A Sudden Gust of Wind, capturing the effects of invisible natural forces on the human body. The girls are rendered against abstract backgrounds with polka dots and other patterns, immersed in a storm of cute clutter: petals, musical notes, stars, candy, school supplies, and colorful Japanese characters. Their world is magical, never-ending, contrasting with the clogged reality of the exhibition space. On canvas, the natural forces of wind and storm are reimagined as telekinetic powers of magical idol singers, surrounded by a fancy goods extravaganza.

Mr.’s windswept girls are a statement “On Being Light and Liquid,” like Zygmunt Bauman’s preface to Liquid Modernity (2000). Bauman’s concept of “liquid modern” describes our time as the chaotic or deregulated continuation of modernity, marked by volatile identities, tailored towards the global flows of neoliberalism. Nomadic, provisional, shifting. There is something “liquid” about Mr.’s girls, too. Their bodies are kaleidoscopic, shattered into an endless profusion of lace, bracelets, rings, scarves, hats, ties, hooks, fabric patterns, and hair arrangements. Against this fluidity, the garbage caterpillar, resting at the center of the gallery space, is an uncomfortable presence conditioning the viewing experience by physically impairing the circulation of visitors. We can see this in the video recordings of the opening of the exhibition.[4] [Figure 8a, b] The visitors squeeze into two lines going in opposite directions, forcing some people to awkwardly bend away from the objects that stick from the main structure, like thorns. As they walk, the assorted paraphernalia captures the visitors’ attention, prompting them to stop, examine, and photograph its details, resulting in pauses, impairments, and human “traffic jams.” Metamorphosis thus underlines the paradoxical process by which fluidity sometimes produces hindrances, both in nature and in capitalist globalization, in the age of “liquid modernity.”

Mr.’s affinity with waste dates to the early years of his career. As an art student, Mr. produced conceptual works out of the garbage that he collected. He was influenced by Arte Povera and the Italian Transvanguardia, as well as Mono-ha (もの派, “School of Things”),[5] a Japanese art movement from the late 1960s and early 1970s whose practices included the juxtaposition of unaltered natural and industrial materials. Much like Metamorphosis’s distribution of elements in space, Mono-ha artists focused as much on the materials as such as on the interdependency among themselves and the surrounding space.[6] Moreover, Mr.’s first Superflat works were drawings of anime girls “on store receipts, takeout menus, and other scraps of transactional detritus,” maintaining a continuity with the poetics of waste and precarity.[7] In Journey, a painting and collage on canvas built over three years from 2003 to 2006, Mr.’s animanga children and quirky kawaii monsters are buried in layers of dirt, [Figure 9] resembling the artworks of Neo-Pop precursor, Shinro Ohtake. Also, in 2008, Mr. built several large-scale dioramas mimicking the vernacular “architecture” of otaku rooms, presented in his solo exhibition The World of “Nobody Dies” at Kaikai Kiki Gallery in Tokyo. [Figure 10] The rooms were cramped and disordered, with stuff everywhere, including manga magazines, crumpled futons, anime posters, discarded items, and electronic appliances, along with artworks such as drawings and photographs, seemingly caught red-handed in their natural material (and psycho-sexual) environment.

In Mr.’s work, cuteness is the enantiodromiac opposite of chaos and self-abjection, the superabundance of the former inevitably changing into its shadow opposite, and vice-versa. But the expression of “trash” is not necessarily fixed upon the literal usage of garbage and debris. As Mr. explains,

“I remember thinking that I am the embodiment of garbage, of the delusions of the post‑war Japanese. And so the reason I continue to expose myself by making these amateurish paintings of cute girls is because this, too, might be a form of Arte Povera, the expression of spiritual poverty… Once I reached that conclusion, that no matter how much work I put in I was still making garbage, I no longer felt the need to use actual trash in my work.”

Since 2011, Mr. has begun to reincorporate actual trash in his work, as in the beginning of his career. In Sunset In My Heart, a more recent solo show at Lehmann Maupin (June 23–August 12, 2016), Mr. presented a series of eleven new paintings over distressed canvases. [Figures 11 & 12] As stated in the press release, “Mr. prepares the canvases by burning them, walking over them, and leaving them on his studio floor to collect dirt and debris,”[9] a practice “directly connected to the artist’s early interest in the 1960s Italian art movement Arte Povera.”[10] The blurb also introduces at length the theme of hope and spirituality in a post‑disaster scenario:

“These new characters represent positive beacons of strength that overcome all adversity. This reflects the artist’s creative impetus to embrace pleasure and beauty in diverse forms, instead of giving in to the personal and national despair that emerges after catastrophic loss and destruction, as it has in Japan since 2011. The title, Sunset in My Heart, reflects the simultaneous yet conflicting feelings of melancholy and hope, which also encompass the complicated nature of the human condition.”

Both Metamorphosis; Give Me Your Wings and Sunset In My Heart exemplify a trend to infuse Superflat artists’ discourse and work with a newfound gravitas after the 3/11 disasters, moving away from commercialism towards more practical or spiritual concerns. However, whereas Metamorphosis was generally well received, Sunset gathered no such acclaim. Probably because, for many art critics, the less Superflat it looks, the better, and Metamorphosis certainly deviates more thoroughly from the Superflat status quo. For instance, the paintings in Metamorphosis are pushed into the background, with even the biggest canvas in the exhibition—a mural-sized painting of a magical idol singer occupying the whole bottom wall—serving as a wallpaper for the garbage caterpillar. [Figure 13] The latter resembles Pistoletto’s enormous piles of clothes, [Figure 14] while the exhibition’s space doubles as an installation channeling the pervasive influence of Scatter Art since the 1990s.

On the contrary, Sunset presents a return to order: just paintings, neatly arranged within the gallery’s white cube: the trash is, once again, integrated with (not separated from) the cuteness. As such, Sunset’s stylistic changes are less noticeable, and the medium of painting, as opposed to installation, perceived to be less radical. This “return to order” substantiates the suspicion that, despite the artists’ claims, the destiny of post-3/11 Superflat is less a rebirth than a zombification, in a struggle to rescue the movement from irrelevance. Indeed, reviewing Sunset, critic Michael Wilson points to this contradiction, writing that,

“The Japanese artist known only as Mr. claims that the 2011 Tohoku earthquake exercised a deep impact on his practice, prompting him to move away from a preoccupation with the sexualized aspects of manga culture toward a more nuanced emotional and political approach. But there’s little evidence of any such let’s-get-serious reappraisal in Mr.’s latest New York outing, which the artist — dressed as a uniformed schoolgirl—launched with a discordant bout of sake-fueled karaoke. In 11 new paintings, Mr. stirs his familiar saucer-eyed cuties into a multicolored abstract and typographic stew that suggests a continued escape into pubescence.”

Wilson’s review suggests that not only is Mr.’s work too Superflat (“familiar saucer-eyed cuties” over a “multicolored abstract and typographic stew”) but the artist, himself, too Japanese. In fact, in Wildon’s view, Mr.’s homage to Arte Povera seems to be the single redeeming quality of Sunset In My Heart: “While [Murakami Takashi] is known for the Koonsian slickness of his ultra-high-end productions, Mr.’s work is distinguished by the use of dirty, distressed canvases, patched together in homage to Arte Povera and its veneration of the everyday.”[13] The notion that the cute, painterly, and Japanese parts of Superflat are tolerated insofar as the un-cute, un-painterly, and un-Japanese parts imbue the works with a proper psychological and artistic depth, is not an uncommon theme in art reviews of Superflat shows. This “dark cute” rhetoric is also promoted by the artists themselves, as attested by Murakami’s artist books-cum-manifestos, Superflat (2000) and Little Boy (2005), that draw a direct line between the spread of the kawaii and what historian Harry Harootunian calls “Japan’s long postwar.”[14] While certainly not all the ramifications of Superflat’s juggling of Western expectations over Japanese artists are deliberate, Murakami and Mr. have nevertheless built an aesthetic corpus conducive to such a cat-and-dog game of fakeness and authenticity, stereotyping and “strategic essentialism” (Gayatri Spivak), which impair the flowy circulation of transcultural dialogues.

For instance, Kris Scheifele, in her analysis of Metamorphosis, makes sense of Mr.’s work by recognizing that “the super cute, Superflat works infuse the accumulation with the deep wounds inflicted by World War II”[15] while also taking the installation medium to prove that “Mr. is clearly… immersed in his source material”, as “viewers are permitted to walk around a… dense collection of clutter in his installation.”[16] One suspects that Mr. deliberately wallows in the fact that the Western art world seems to crave a radical materialism insofar as artists and works fit within the mold of the “colonized copy,”[17] e.g., using the familiar vocabulary of Arte Povera and Scatter Art, while other kinds of “radical materialism,” like karaoke and crossplay, are readily discarded as “Wacky Japan.”[18] Indeed, the title of Mr.’s recent exhibition at Perrotin Hong Kong (September 14 – October 20, 2018) feels like a provocation targeted at such prescriptive identities afforded to Japanese artists: PEOPLE MISUNDERSTAND ME AND THE CONTENTS OF MY PAINTINGS. THEY JUST THINK THEY ARE NOSTALGIC, CUTE, AND LOOK LIKE JAPANESE ANIME. THAT MAY BE TRUE, BUT REALLY, I PAINT DAILY IN ORDER TO ESCAPE THE DEVIL THAT HAUNTS MY SOUL. THE SAID DEVIL ALSO RESIDES IN MY BLOOD, AND I CANNOT ESCAPE FROM IT NO MATTER HOW I WISH. SO I PAINT IN RESIGNATION.[19]

Mr. has continued to explore the formats of Metamorphosis and Sunset in other recent exhibitions. For instance, Tokyo, The City I Know, at Dusk: It’s Like a Hollow in My Heart (Perrotin Seoul, 2016) and his art intervention the Yokohama Triennale in 2017. [Figure 15] Tokyo is a “total installation” transforming the gallery into an immersive environment, with graffiti, paint scrapes, and debris defacing the entirety of the white, including ceiling and floor, as if the damage inflicted to the paintings in Sunset now overflows the canvas’ boundaries, exploding into the expanded field of a “rubbish ecology”[20] of kawaii culture and aesthetics. These environments expand on the otaku room dioramas in The World of “Nobody Dies” (2008), that resembled Mr.’s own house and studio in the outskirts of Tokyo. As seen in the tour for the website The Selby, Mr.’s otaku room is filled with manga magazines, idol books, improvised futon, studies for paintings, drawings, cup noodles, merchandise, and clothing. [Figure 16] In drawing from the private and collective space management of the otaku, who for decades were the pariahs of Japanese society, Mr.’s work aligns with a lineage of installations like those of artist Hélio Oiticica, who drew from the vernacular architecture of the Brazilian favelas in his environments from the 1960s such as Tropicália (1967). [Figure 17a, b, c, d] Significantly, the otaku environments in Mr.’s works are not represented merely as the result of overconsumption, but also as a hub of creation, true to the nature of the otaku subculture as a historical site of “produsage” (e.g., user-led content creation, such as fan illustrations, fan manga, and fan fiction).

There is also an unresolved tension between painting and installation at work in Metamorphosis and other Mr. exhibitions. Is the installation a setting for painting, or are paintings like props within the installation? Such duality problematizes the spatial contradictions for which the otaku are known in the collective imagination. While the otaku often take obsessive care in organizing and safekeeping their collections of figures and books, the prioritizing of fantasy over basic human needs for comfort and space results in rooms filled with garbage and scattered goods. In old-school media representations of otaku rooms, these overlap with compulsive hoarding and other disordered states, like the bachelor pad: a messy man cave with clothes and trash on the floor and rotten food in the fridge. [Figure 18] These dirty spaces are also a reflection of the otaku’s “polluted” libido, fueled by an underlying Lolita Complex that taints even supposedly desexualized genres like moé, and seems to extend spatially to the advertising overload displayed outside and inside buildings in Tokyo’s district of Akihabara (known as the otaku Mecca).

Nevertheless, in Mr.’s environments one gets the impression that the otaku’s apparently dysfunctional and “polluted” management of space can become a valuable survival skill for the advanced capitalist jungle—along with that of other marginalized groups, like the numerous homeless living in tent villages, unacknowledged by the official rhetoric of classless Japan. [Figure 19] In fact, 24-hour Internet or manga cafés (mangakissa) are a shared space among the otaku and the homeless. [Figure 20] These coffeehouses, offering comics and Internet for an affordable hourly fee (some even providing showers, underwear, snack/beverage vending machines),[21] have given rise to a new class of homeless known as “net café refugees” or “cyber-homeless.”[22] These tent and cyber refugees exhibit a nomadic quality akin to that of Mr.’s garbage caterpillar in Metamorphosis, a strange caravan moving towards our dystopian futures.

Mr.’s Metamorphosis captures the “dream scenes” of otaku rooms. According to Claire Bishop, “the idea of the ‘total installation’ offers a very particular model of viewing experience—one that not only physically immerses the viewer in a three-dimensional space, but which is psychologically absorptive too.”[23] In the otaku room, however, despite its absorptiveness, it is not uncommon for figures and other the collectibles to be stored in glass cabinets or kept inside their packages, protected from human contact. Engulfed by fantasy, the otaku remains separated from it as if by an invisible veil, always to some extent impenetrable. In this sense, Metamorphosis also calls to mind Ilya Kabakov’s 1985 installation The Man Who Flew into Space from his Apartment, [24] in which Kabakov recreated the room of a fictional artist, filling the walls with Soviet propaganda. [Figure 21a, b] Inside the cabin, Kabakov’s fictional artist built a catapult that, judging by the hole in the ceiling, had propelled him into outer space. “He didn’t want to wait until the whole of the rest of society was ready for utopia,” Boris Groys writes. “He wanted to head off for utopia there and then.”[25] Mr. is less interested in science fiction—after all, space sagas like Uchū Senkan Yamato (Space Battleship Yamato) and Gundam are the turfs of the first-generation otaku, before the “moé-fication” of otaku culture in the 2000s. But significantly, in both Metamorphosis; Give Me Your Wings and The Man Who Flew into Space from his Apartment, the dream scene is overlapped with the crime scene.

On the one hand, Kabakov’s artist is a rogue cosmonaut unsanctioned by the authorities. On the other, Metamorphosis, in adhering to the cramped, but absorptive spatiality of otaku rooms, evokes the specter of the otaku murder, Miyazaki Tsutomu, a serial killer who brutally murdered four girls. Miyazaki’s tiny room crammed with thousands of VHS tapes and manga magazines became an icon of the otaku’s deviancy in Japanese society; one that, despite over a decade of Cool Japan campaigns, never entirely faded from the Japanese collective consciousness. Is the dream scene’s potential to turn nightmarish—even, diabolical—what, in Mr.’s words, haunts his blood and his soul? Or its uncanny capacity to devour us, to dilute one’s sense of self in the muddled, if spectacular, boundaries of fantasy and reality? Ultimately, The Man Who Flew into Space and Metamorphosis represent the ruins and remnants left behind in humanity’s quest for utopia at a time of looming disaster, when, as Fredric Jameson first put it in Seeds of Time, “It seems to be easier for us… to imagine the thoroughgoing deterioration of the earth and of nature than the breakdown of late capitalism.”[26] Respectively, the techno-scientific utopia of the Soviet space program, and the emotional utopia of moé’s 2D “love revolution,”[27] i.e., the ability to adore and fall in love with idealized fictional characters in stress and anxiety-free (no longer intersubjective, but interobjective) relations.

See in CUTENCYCLOPEDIA – Gesamptcutewerk & It Girl.

REFERENCES in Metamorphosis.

Figure 1a View of Mr.’s Metamorphosis; Give Me Your Wings at Lehmann Maupin gallery in New York, 2012. Source.

Figure 1b View of Mr.’s Metamorphosis; Give Me Your Wings. Source.

Figure 2 View of Metamorphosis; Give Me Your Wings with graffiti, photographs, drawings, and trash. Source.

Figure 3 "“Island” of debris resulting from the 2011 tsunami. Photo by the U.S. Navy. Source.

Figure 4a Nooks and details from Metamorphosis; Give Me Your Wings. Source.

Figure 4b More details. Source.

Figure 5 View from Metamorphosis; Give Me Your Wings with a photograph of food leftovers photograph on the wall. Source.

Figure 6 Close-up of a sketch in Metamorphosis; Give Me Your Wings. Source.

Figure 7a Mr., Like A Dream That Never Ends, 2012. Acrylic and string on canvas mounted on an aluminium frame, 130.5 x 130.2 x 4.1 cm. Source.

Figure 7b Mr., Storm Of Flowers, 2012. Acrylic on canvas, 116.7 x 80.3 cm. Source.

Figure 8a Human “traffic jam” in Metamorphosis; Give Me Your Wings. Source: LM Artist Video Series: Mr., Metamorphosis: Give Me Your Wings (New York; Lehmann Maupin Gallery), 2012.

Figure 8b More human “jams” in Metamorphosis; Give Me Your Wings. Source.

Figure 9 Detail of Journey (2003–2006), an example of an earlier painting in which the cute figures appear in an environment of dirt and disintegration. Photo by Éric Simon. Source.

Figure 10 View of an otaku room in Mr.’s The World of “Nobody Dies,” titled Mr.’s Room 2. Photo by Kurage Kikuchi. Source.

Figure 11 View of Mr.’s solo show Sunset in My Heart at Lehmann Maupin in New York, 2016. Source.

Figure 12 Detail of a painting from Sunset in My Heart. Mr., Pinkish Gold (detail), 2016. Acrylic and pencil on canvas mounted on wooden panel, 162.7 x 130.4 x 5.5 cm. Source.

Figure 13 View of large-sized painting in Metamorphosis; Give Me Your Wings. Source.

Figure 14 Mountain of clothes by Italian Arte Povera artist Michelangelo Pistoletto. Source.

Figure 15View of Mr.’s solo show Tokyo, The City I Know, at Dusk: It’s Like a Hollow in My Heart at gallery Perrotin Seoul, in 2016. Source.

Figure 17a Detail of Metamorphosis; Give Me Your Wings showing manga magazines among boxes and household goods. Source: LM Artist Video Series: Mr., Metamorphosis: Give Me Your Wings (New York; Lehmann Maupin Gallery), 2012.

Figure 17b An otaku shut-in’s room in disorder. Source.

Figure 17c Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica’s installation Tropicália, 1967. Plants, sand, stones, macaws, television set, fabric, and wood. Photo by César Oiticica. Source.

Figure 17d View of a favela in Brazil. Source.

Figure 18 A panel from the Kio Shimoku’s manga series Genshiken, ran from April 25, 2002, to May 25, 2006, in the comics magazine Afternoon, published by Kodansha. In this series about otaku cultures, Kōsaka Makoto (the blond boy on the left) is a character on the threshold between old-school otaku and “otacool”: he is handsome and fashionable on the outside, but his house remains the messy bachelor pad typical of otaku caricatures. Sasahara Kanji, the main character, admires his friend’s unselfconsciousness about his otaku lifestyle (hence, “what I lack is the courage to accept myself for who I am”).

Figure 19 A homeless “tent city” in Osaka. Source.

Figure 20 Luminous sign of a mangakissa (manga and internet cafe). Source.

Figure 21a View of Ilya Kabakov’s 1985 installation The Man Who Flew into Space from his Apartment at the exhibition El Lissitzky – Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, at Kunsthaus Graz, Austria, in 2013. Source.

Figure 21b View of The Man Who Flew into Space from his Apartment, 1985. Source.

ABSOLUTE BOYFRIEND ; (BETAMALE) ; BLINGEE ; CGDCT ; CREEPYPASTA ; DARK WEB BAKE SALE ; END, THE ; FAIRIES ; FLOATING DAKIMAKURA ; GAIJIN MANGAKA ; GAKKOGURASHI ; GESAMPTCUTEWERK; GRIMES, NOKIA, YOLANDI ; HAMSTER ; HIRO UNIVERSE ; IKA-TAKO VIRUS ; IT GIRL ; METAMORPHOSIS ; NOTHING THAT’S REALLY THERE; PARADOG ; PASTEL TURN ; POISON GIRLS ; POPPY ; RED TOAD TUMBLR POST ; SHE’S NOT YOUR WAIFU, SHE’S AN ELDRITCH ABOMINATION ; ZOMBIEFLAT