[1] Elizabeth Legge, ‘When Awe Turns to Awww... Jeff Koon’s Balloon Dog and the Cute Sublime’, in The Aesthetics and Affects of Cuteness, ed. Joshua Paul Dale et al. (New York: Routledge, 2016), 142.

[2] Rosalind E. Krauss and Yve-Alain Bois, Formless: A User’s Guide (New York: Zone Books, 1997), 16.

[3] Krauss and Bois, 16.

[4] Ernest L. Boyer, Scholarship Reconsidered: Priorities of the Professoriate (Princeton, NJ: Jossey-Bass, 1997), 19.

[5] Boyer, 18–19.

[6] Krauss and Bois, Formless, 18–21.

[7] Stephanie Bowry, ‘Before Museums: The Curiosity Cabinet as Metamorphe’, Museological Review 18 (1 January 2014): 36–37.

[8] Bowry, 39.

[9] Jussi Parikka, ‘New Materialism as Media Theory: Medianatures and Dirty Matter’, Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 9, no. 1 (March 2012): 96, https://doi.org/10.1080/14791420.2011.626252.

[10] Sianne Ngai, ‘The Cuteness of the Avant‐Garde’, Critical Inquiry 31, no. 4 (2005): 816, https://doi.org/10.1086/444516.

[11] Mark Mitchell, ‘Japonisme, Japonaiserie and Chinoiserie’, The Art Blog by Mark Mitchell (blog), 27 February 2014, https://www.markmitchellpaintings.com/blog/japonisme-japonaiserie-and-chinoiserie/.

[12] Wester Wagenaar, ‘Wacky Japan: : A New Face of Orientalism’, Asia in Focus: A Nordic Journal on Asia by Early Career Researchers, no. 3 (2016): 46–54.

[13] ‘Moe Anthropomorphism’, in Wikipedia, 17 April 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Moe_anthropomorphism&oldid=836931650.

[14] ‘Moe Anthropomorphism’.

[15] Thomas Lamarre, ‘Introduction’, in Mechademia 6: User Enhanced, ed. Frenchy Lunning (Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), ix–x..

[16] Kanako Shiokawa, ‘Cute but Deadly: Women and Violence in Japanese Comics’, in Themes and Issues in Asian Cartooning: Cute, Cheap, Mad, and Sexy, ed. John A. Lent (Bowling Green, OH: Popular Press 1, 1999), 120.

[17] ‘The Appeal of the Cute Object: Desire, Domestication, and Agency’, in The Aesthetics and Affects of Cuteness, ed. Joshua Paul Dale et al. (New York: Routledge, 2016), 35.

[18] Casey Brienza, ‘Manga without Japan?’, in Global Manga: ‘Japanese’ Comics without Japan?, ed. Casey Brienza, 2015, 1.

[19] Brienza, 4.

[20] Tomiko Yoda, ‘A Roadmap to Millenial Japan’, in Japan After Japan: Social and Cultural Life from the Recessionary 1990s to the Present, ed. Tomiko Yoda and Harry Harootunian (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2006), 46.

[21] Alisa Freedman and Toby Slade, ‘Introducing Japanese Culture: Serious Approaches to Playful Delights’, in Introducing Japanese Popular Culture, ed. Alisa Freedman and Toby Slade (Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge, 2017), 347.

[22] Throughout this dissertation, I use the term “animanga” to indicate the joint products and culture of anime (Japanese animation) and manga (Japanese comics), as well as directly related products that are often adapted and informed by these media, such as light novels (novels with anime-style illustrations) and visual novels (anime-style videogames reseambling Western adventure games).

[23] Joshua Paul Dale, ‘Cute Studies: An Emerging Field’, Text, 1 April 2016, https://doi.org/info:doi/10.1386/eapc.2.1.5_2.

[24] Sianne Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting (London; Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2012), 1.

[25] Sianne Ngai, Ugly Feelings (Harvard University Press, 2007), 6.

[26] Throughout this dissertation, the names of people and characters originating from Japan will be presented in the Japanese order, in which the surname comes before the given name (unless they explicitally manifest a preference otherwise). Although many Japanese artists and scholars working internationally adopt the Western name/ surname order (as is the case of Takashi Murakami and Yoshitomo Nara), I have opted for this solution in the interest of consistency, as it avoids the confusion of having some Japanese names in Japanese order and others in Western order.

[27] Joshua Paul Dale et al., eds., The Aesthetics and Affects of Cuteness (New York: Routledge, 2016), 2.

[28] Dale et al., 2.

[29] Dale et al., The Aesthetics and Affects of Cuteness.

[30] Dale, ‘The Appeal of the Cute Object: Desire, Domestication, and Agency’, 37.

[31] Dale, 36.

[32] Dale, ‘Cute Studies’, 5.

[33] Ian Sample, ‘How Canines Capture Your Heart: Scientists Explain Puppy Dog Eyes’, The Guardian, 17 June 2019, sec. Science, paras.2-4, https://www.theguardian.com/science/2019/jun/17/how-dogs-capture-your-heart-evolution-puppy-dog-eyes.

[34] Dale, ‘The Appeal of the Cute Object: Desire, Domestication, and Agency’, 50–51.

[35] Dale, 46–51.

[36] Dale et al., The Aesthetics and Affects of Cuteness, 2.

[37] Gary Cross, The Cute and the Cool: Wondrous Innocence and Modern American Children’s Culture (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 43.

[38] Ngai, ‘The Cuteness of the Avant‐Garde’, 827.

[39] Legge, ‘When Awe Turns to Awww... Jeff Koon’s Balloon Dog and the Cute Sublime’, 142.

[40] Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories, 2012, 64.

[41] Brandon LaBelle, Sonic Agency: Sound and Emergent Forms of Resistance (London: Goldsmiths Press, 2018), 151.

[42] Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories, 2012, 64.

[43] Ngai, 65.

[44] Ngai, ‘The Cuteness of the Avant‐Garde’, 816.

[45] Andreas Huyssen, After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987), viii.

[46] Andreas Huyssen, ‘High/Low in an Expanded Field’, Modernism/Modernity 9, no. 3 (1 September 2002): 367, https://doi.org/10.1353/mod.2002.0052.

[47] Cross, The Cute and the Cool, 44.

[48] David Ehrlich, ‘From Kewpies to Minions: A Brief History of Pop Culture Cuteness - Rolling Stone’, Rolling Stone, 21 July 2015, par. 2, http://www.rollingstone.com/movies/news/from-kewpies-to-minions-a-brief-history-of-pop-culture-cuteness-20150721.

[49] Sianne Ngai, ‘Our Aesthetic Categories’, PMLA 125, no. 4 (1 October 2010): 948, https://doi.org/10.1632/pmla.2010.125.4.948.

[50] Cross, The Cute and the Cool.

[51] Ngai, ‘Our Aesthetic Categories’, 1 October 2010, 817.

[52] Cross, The Cute and the Cool, 43.

[53] Cross, 47–48.

[54] Margaret Drabble, ed., The Oxford Companion to English Literature (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 261.

[55] Cross, The Cute and the Cool, 44.

[56] Cross, 51.

[57] Dale, ‘Cute Studies’, 6.

[58] Shiokawa, ‘Cute but Deadly: Women and Violence in Japanese Comics’, 120.

[59] Mark Serrels, ‘Why Women Want To Have Sex With Garrus’, Kotaku, 27 March 2017, http://kotaku.com/why-women-want-to-have-sex-with-garrus-1793662351.

[60] Colin Schultz, ‘In Defense of the Blobfish: Why the “World’s Ugliest Animal” Isn’t as Ugly as You Think It Is’, Smithsonian, 13 September 2013, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/in-defense-of-the-blobfish-why-the-worlds-ugliest-animal-isnt-as-ugly-as-you-think-it-is-6676336/.

[61] Elaine M. Laforteza, ‘Cute-Ifying Disability: Lil Bub, the Celebrity Cat’, M/C Journal 17, no. 2 (18 February 2014), http://journal.media-culture.org.au/index.php/mcjournal/article/view/784.

[62] Shiokawa, ‘Cute but Deadly: Women and Violence in Japanese Comics’, 121.

[63] Dale, ‘The Appeal of the Cute Object: Desire, Domestication, and Agency’, 39.

[64] Rina Arya, Abjection and Representation: An Exploration of Abjection in the Visual Arts, Film and Literature (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 125.

[65] ‘Abicio’, in Wiktionary, accessed 4 October 2017, https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/abicio#Latin.

[66] Arya, Abjection and Representation, 190.

[67] Arya, 2.

[68] Arya, 3–4.

[69] Arya, 3–4.

[70] ‘The Cuteness of the Avant‐Garde’, 838.

[71] Hal Foster et al., ‘The Politics of the Signifier II: A Conversation on the “Informe” and the Abject’, October 67 (1994): 3–21.

[72] Krauss and Bois, Formless, 245.

[73] Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), 2.

[74] Visions Of Excess: Selected Writings, 1927-1939, ed. Allan Stoekl (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985), 31.

[75] Fred Botting, ‘Dark Materialism’, Backdoor Broadcasting Company (blog), 2011, par. 1, http://backdoorbroadcasting.net/2011/01/dark-materialism/.

[76] Krauss and Bois, Formless, 244.

[77] Nicholas Royle, The Uncanny (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2011), 1.

[78] Luke Thurston, ‘Ineluctable Nodalities: On the Borromean Knot’, in Key Concepts of Lacanian Theory, ed. Dany Nobus (New York: Other Press, 1998).

[79] Jacques-Alain Miller, ‘Extimité’, in Lacanian Theory of Discourse: Subject, Structure, and Society, ed. Mark Bracher (New York: NYU Press, 1997), 76.

[80] The Weird and the Eerie (London: Repeater, 2017), 10.

[81] Fisher, 10.

[82] Fisher, 11.

[83] M. Mori, K. F. MacDorman, and N. Kageki, ‘The Uncanny Valley [From the Field]’, IEEE Robotics Automation Magazine 19, no. 2 (June 2012): ‘Editor’s Note’, https://doi.org/10.1109/MRA.2012.2192811.

[84] ‘PARO Therapeutic Robot’, accessed 24 April 2019, http://www.parorobots.com/.

[85] Adam Piore, ‘Will Your Next Best Friend Be A Robot?’, Popular Science (blog), 18 November 2014, par. 39, https://www.popsci.com/article/technology/will-your-next-best-friend-be-robot.

[86] Miriam Silverberg, Erotic Grotesque Nonsense: The Mass Culture of Japanese Modern Times (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 1–9.

[87] Casey Baseel, ‘Japan’s Unbelievably Buff Muscle Idol Shares Workout Videos, Performs Wicked Clothesline’, SoraNews24 (blog), 9 May 2019, par. 8, https://soranews24.com/2019/05/10/japans-unbelievable-buff-muscle-idol-shares-workout-videos-performs-wicked-clothesline%e3%80%90videos%e3%80%91/.

[88] Brian Ashcraft, ‘This Isn’t Kawaii. It’s Disturbing.’, Kotaku, 23 August 2012, http://kotaku.com/5937180/this-isnt-kawaii-its-disturbing; Patrick St. Michel, ‘The Rise of Japan’s Creepy-Cute Craze’, The Atlantic, 14 April 2014, https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2014/04/the-rise-of-japans-creepy-cute-craze/360479/; Preston Phro, ‘Itami-Kawaii: Cute Gets Depressing, Inspires Japanese Twitter Users’, SoraNews24 (blog), 24 February 2015, https://soranews24.com/2015/02/24/itami-kawaii-cute-gets-depressing-inspires-japanese-twitter-users/; Omri Wallach, ‘Yamikawaii — Japan’s Darker and Cuter Version of Emo’, Medium (blog), 6 March 2017, https://medium.com/@omriwallach/yamikawaii-japans-darker-and-cuter-version-of-emo-d5c7a63af1f4.

[89] John R. Clark, The Modern Satiric Grotesque and Its Traditions (Lexington, Ky: University Press of Kentucky, 1991), 18.

[90] Hrag Vartanian, ‘A Startling Choice, Lisa Frank Is Selected for the US Pavilion at the 2021 Venice Biennale’, Hyperallergic, 1 April 2019, para. 1, https://hyperallergic.com/492709/lisa-frank-2021-venice-biennale/.

[91] Kerstin Mey, Art and Obscenity (London; New York, NY: I.B.Tauris, 2007), 5–6.

[92] Mey, 6.

[93] Mey, 9.

[94] ‘What Is Obscenity Law? | Becoming an Obscenity Lawyer’, accessed 21 April 2019, https://legalcareerpath.com/obscenity-law/; ‘Art on Trial: Obscenity and Art: Nudity’, accessed 21 April 2019, https://www.tjcenter.org/ArtOnTrial/obscenity.html.

[95] Hiroshi Aoyagi and Shu Min Yuen, ‘When Erotic Meets Cute: Erokawa and the Public Expression of Female Sexuality in Contemporary Japan’, Text, 1 April 2016, 99, https://doi.org/info:doi/10.1386/eapc.2.1.97_1.

[96] Barry Smith and Carolyn Korsmeyer, eds., ‘Visceral Values: Aurel Kolnai on Disgust’, in On Disgust (Chicago: Open Court, 2004), 1.

[97] Smith and Korsmeyer, 2.

[98] Smith and Korsmeyer, 23.

[99] On Disgust, ed. Barry Smith and Carolyn Korsmeyer (Chicago: Open Court, 2004), 71.

[100] The Aesthetics and Affects of Cuteness, 42.

[101] Dale, ‘The Appeal of the Cute Object: Desire, Domestication, and Agency’, 41.

[102] Ngai, ‘The Cuteness of the Avant‐Garde’, 827.

[103] On Disgust, 71.

[104] Ngai, ‘The Cuteness of the Avant‐Garde’, 827–28.

[105] One Step Beyond: The Making of ‘Alien: Resurrection’, accessed 24 April 2019, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0387469/.

[106] Parikka, ‘Medianatures’, 99.

[107] ‘Revenge and Recapitation in Recessionary Japan’, in Japan After Japan: Social and Cultural Life from the Recessionary 1990s to the Present, ed. Tomiko Yoda and Harry Harootunian (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2006), 95.

[108] ‘顔映し’, in Wiktionary, accessed 30 August 2017, https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/%E9%A1%94%E6%98%A0%E3%81%97#cite_ref-KDJ_1-0.

[109] Shiokawa, ‘Cute but Deadly: Women and Violence in Japanese Comics’, 95; Adrian David Cheok, Art and Technology of Entertainment Computing and Communication (London ; New York: Springer, 2010), 225; Adrian David Cheok, ‘Kawaii: Cute Interactive Media’, in Imagery in the 21st Century, ed. Oliver Grau and Thomas Veigl (Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 2011), 247.

[110] Shiokawa, ‘Cute but Deadly: Women and Violence in Japanese Comics’, 95.

[111] Shiokawa, 95.

[112] Cheok, Art and Technology of Entertainment Computing and Communication, 225; Cheok, ‘Kawaii: Cute Interactive Media’, 247.

[113] ‘Cute but Deadly: Women and Violence in Japanese Comics’, 95.

[114] Dale, ‘The Appeal of the Cute Object: Desire, Domestication, and Agency’, 39.

[115] ‘Cuties in Japan’, in Women, Media, and Consumption in Japan, ed. Lise Skov and Brian Moeran, (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1996), 236.

[116] Debra Occhi, ‘Wobbly Aesthetics, Performance, and Message: Comparing Japanese Kyara with Their Anthropomorphic Forebears’, Asian Ethnology 71, no. 1 (2012): 113.

[117] Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories, 2012, 85–86.

[118] Wallach, ‘Yamikawaii — Japan’s Darker and Cuter Version of Emo’, par. 2.

[119] Harry Harootunian, ‘Japan’s Long Postwar: The Trick of Memory and the Ruse of History’, in Japan After Japan: Social and Cultural Life from the Recessionary 1990s to the Present, ed. Tomiko Yoda and Harry Harootunian (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2006), 97.

[120] Harootunian, 102.

[121] Daryush Shayegan, Cultural Schizophrenia: Islamic Societies Confronting the West (Syracuse, N.Y: Syracuse University Press, 1997), http://repository.wellesley.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1110&context=scholarship.

[122] Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present, 2nd Edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 17.

[123] John W. Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000), 43.

[124] Dower, 550.

[125] Dower, 551–52.

[126] Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 2011), 227.

[127] In 1986, the average Japanese worker worked 2150 hours, against 1924 of the American worker and 1643 of the French worker; of the fifteen vacation days to which he was entitled, they used only seven. In a 1988 government survey, more than half of the respondents said they preferred more free time to a salary increase.

[128] Gregor Jansen et al., The Japanese Experience: Inevitable, ed. Margrit Brehm (Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany : New York, N.Y: Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2003), 12.

[129] Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present, 2nd Edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 276; Eiji Oguma, ‘Japan’s 1968: A Collective Reaction to Rapid Economic Growth in an Age of Turmoil’, trans. Nick Kapur, Samuel Malissa, and Stephen Poland, The Asia-Pacific Journal, 23 March 2015, http://apjjf.org/2015/13/11/Oguma-Eiji/4300.html.

[130] Michiya Shimbori et al., ‘Japanese Student Activism in the 1970s’, Higher Education 9, no. 2 (1 March 1980): 139, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01680430.

[131] Shimbori et al., 140, 142.

[132] Takashi Murakami, Superflat (Tokyo: Madora Shuppan, 2000), 19.

[133] William W. Kelly, ‘Finding a Place in Metropolitan Japan: Ideologies, Institutions, and Everyday Life’, in Postwar Japan as History, ed. Andrew Gordon (Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 1993), 198.

[134] Kinsella, ‘Cuties in Japan’, 242–43, 251.

[135] Tomiko Yoda, ‘The Rise and Fall of Maternal Society: Gender, Labor, and Capital in Contemporary Japan’, in Japan After Japan: Social and Cultural Life from the Recessionary 1990s to the Present, ed. Tomiko Yoda and Harry Harootunian (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2006), 247, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/30686.

[136] ‘Cuties in Japan’, 250–51; Adult Manga: Culture and Power in Contemporary Japanese Society (Richmond, Surrey: Routledge, 2000), 32.

[137] Ilya Garger, ‘Global Psyche: One Nation Under Cute’, Psychology Today, 1 March 2017, http://www.psychologytoday.com/articles/200703/global-psyche-one-nation-under-cute.

[138] Takashi Murakami, Little Boy: The Art of Japan’s Exploding Subculture (New York; New Haven: Japan Society, Inc. / Yale University Press, 2005), 100.

[139] Kinsella, ‘Cuties in Japan’.

[140] Kinsella, 225.

[141] Susan O. Long, ‘The Society and Its Environment’, in Japan: A Country Study, ed. Ronald E. Dolan and Robert L. Worden (Washington D.C.: United States Government Printing, 1991), 95.

[142] Long, 96.

[143] Kinsella, ‘Cuties in Japan’, 243.

[144] Kinsella, 242–43.

[145] Kinsella, 143.

[146] LaBelle, Sonic Agency, 129.

[147] Masao Miyoshi and Harry Harootunian, ‘Introduction’, in Postmodernism and Japan, ed. Masao Miyoshi and Harry Harootunian (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 1989), xi.

[148] Yoda, ‘A Roadmap to Millenial Japan’, 33.

[149] Miyoshi and Harootunian, ‘Introduction’, viii–ix.

[150] Miyoshi and Harootunian, xii.

[151] Introduction to the Reading of Hegel: Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit, ed. Allan Bloom, trans. James H. Nichols (Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press, 1980), 162.

[152] Koichi Iwabuchi, ‘Complicit Exoticism: Japan and Its Other’, Continuum 8, no. 2 (1 January 1994): 49–82, https://doi.org/10.1080/10304319409365669.

[153] Murakami, Superflat, 5.

[154] Marilyn Ivy, ‘Critical Texts, Mass Artifacts: The Consumption of Knowledge in Postmodern Japan’, in Postmodernism and Japan, ed. Masao Miyoshi and Harry Harootunian (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 1989), 21.

[155] Ivy, 26–33; W. David Marx, ‘Structure and Power (1983)’, Néojaponisme (blog), 6 May 2011, paras. 1-2, https://neojaponisme.com/2011/05/06/structure-and-power-1983/.

[156] Yoda, ‘A Roadmap to Millenial Japan’, 34.

[157] Yoda, 34.

[158] Yoda, 36–37, 44–45, 47.

[159] Yoda, 44.

[160] Murakami, Superflat, 19–23.

[161] Adrian Favell, Before and after Superflat: A Short History of Japanese Contemporary Art, 1990-2011 (Hong Kong: Blue Kingfisher, 2011), 68, http://www.adrianfavell.com/BASF%20MS.pdf.

[162] Ivy, ‘Critical Texts, Mass Artifacts: The Consumption of Knowledge in Postmodern Japan’, 33, 36.

[163] Favell, Before and after Superflat, 65.

[164] Kristen Sharp, ‘Superflatworlds : A Topography of Takashi Murakami and the Cultures of Superflat Art’, 2006, 102, https://researchbank.rmit.edu.au/view/rmit:9886.

[165] Takashi Murakami, ‘A Message:Laying the Foundation for a Japanese Art Market’, Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd., accessed 12 October 2017, http://english.kaikaikiki.co.jp/whatskaikaikiki/message/.

[166] Favell, Before and after Superflat, 65.

[167] GARAGEMCA, Transculturation, Cultural Inter-Nationalism and beyond. A Lecture by Koichi Iwabuchi at Garage, YouTube video (Moscow: Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2018), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ckebrWCgmeA.

[168] Adrian Favell, ‘Aida Makoto: Notes from an Apathetic Continent’, in Introducing Japanese Popular Culture, ed. Alisa Freedman and Toby Slade (Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge, 2017), loc. 9551; Favell, Before and after Superflat, 224.

[169] Jonathan Yee and Eileen Kinsella, ‘Why Collectors Love Takashi Murakami, Part 2’, artnet News, 14 November 2014, https://news.artnet.com/market/art-market-analysis-why-collectors-love-takashi-murakami-part-2-162123.

[170] Christine R. Yano, ‘Flipping Kitty: Transnational Transgressions of Japanese Cute’, in Medi@sia: Global Media/Tion in and Out of Context, ed. T. J. M. Holden and Timothy J. Scrase (London u.a.: Routledge, 2006), 2008.

[171] ‘The Kawaii Ambassadors (Ambassadors of Cuteness)’, Web Japan, August 2009, http://web-japan.org/trends/09_culture/pop090827.html.

[172] Discourses of the Vanishing: Modernity, Phantasm, Japan (Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 1995), 1.

[173] GARAGEMCA, Transculturation, Cultural Inter-Nationalism and beyond. A Lecture by Koichi Iwabuchi at Garage, 41:55.

[174] GARAGEMCA, 41:55.

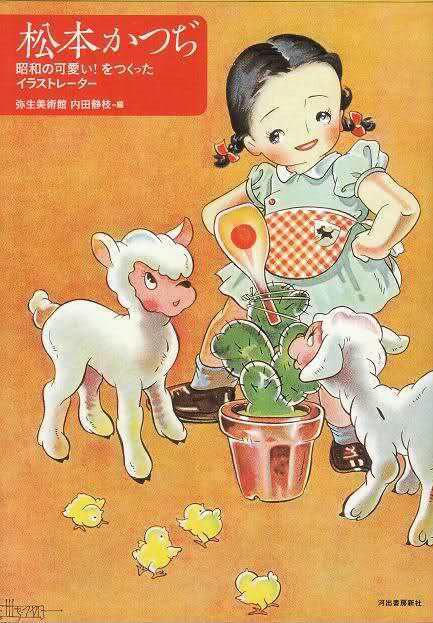

[175] Ryan Holmberg, ‘Matsumoto Katsuji and the American Roots of Kawaii’, The Comics Journal (blog), 7 April 2014, par. 3, http://www.tcj.com/matsumoto-katsuji-and-the-american-roots-of-kawaii/.

[176] ‘Katsuji Matsumoto’, The Manga (blog), 15 January 2015, http://ngembed-manga.blogspot.com/2015/01/katsuji-matsumoto_15.html.

[177] Cross, The Cute and the Cool, 43–81.

[178] Holmberg, ‘Matsumoto Katsuji and the American Roots of Kawaii’, paras. 7, 15.

[179] Ryan Holmberg, ‘Matsumoto Katsuji: Modern Tomboys and Early Shojo Manga’, in Women’s Manga in Asia and Beyond: Uniting Different Cultures and Identities, ed. Fusami Ogi et al. (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 200.

[180] ‘Katsuji Matsumoto’, in Wikipedia, 14 August 2018, ‘Kurukuru Kurumi-chan’, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Katsuji_Matsumoto&oldid=854885031.

[181] Marco Pellitteri, The Dragon and the Dazzle: Models, Strategies, and Identities of Japanese Imagination: A European Perspective (John Libbey Publishing, 2011), 79.

[182] Barbara Hartley, ‘Performing the Nation: Magazine Images of Women and Girls in the Illustrations of Takabatake Kashō, 1925–1937’, Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific, no. 16 (March 2008), http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue16/hartley.htm.

[183] Holmberg, ‘Matsumoto Katsuji and the American Roots of Kawaii’; Hartley, ‘Performing the Nation: Magazine Images of Women and Girls in the Illustrations of Takabatake Kashō, 1925–1937’.

[184] Eico Hanamura, Eico Hanamura, interview by Manami Okazaki and Geoff Johnson, Kawaii!! Japan’s Culture of Cute [book], 2013, 26, https://www.amazon.com/Kawaii-Japans-Culture-Manami-Okazaki/dp/3791347276.

[185] Nozomi Masuda, ‘Shojo Manga and Its Acceptance: What Is the Power of Shojo Manga’, in International Perspectives on Shojo and Shojo Manga: The Influence of Girl Culture, ed. Masami Toku (New York ; London: Routledge, 2015), 24.

[186] Hanamura, Eico Hanamura, 21.

[187] Deborah M. Shamoon, Passionate Friendship: The Aesthetics of Girl’s Culture in Japan (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2012).

[188] Macoto Takahashi, Macoto Takahashi, interview by Manami Okazaki and Geoff Johnson, Kawaii!! Japan’s Culture of Cute [book], 2013, 28, https://www.amazon.com/Kawaii-Japans-Culture-Manami-Okazaki/dp/3791347276.

[189] Rachel ‘Matt’ Thorn, ‘Before the Forty-Niners’, rachel-matt-thorn-en, 12 June 2017, para. 7, https://www.en.matt-thorn.com/single-post/2017/06/12/Before-the-Forty-Niners.

[190] Takahashi, Macoto Takahashi, 28.

[191] ‘TAKAHASHI Makoto’, Baka-Updates Manga, accessed 14 October 2017, https://www.mangaupdates.com/authors.html?id=7263.

[192] Shiokawa, ‘Cute but Deadly: Women and Violence in Japanese Comics’, 101.

[193] Shiokawa, 101.

[194] Natsu Onoda Power, God of Comics: Osamu Tezuka and the Creation of Post-World War II Manga (Jackson Miss.: University Press of Mississippi, 2009); Helen McCarthy and Katsuhiro Otomo, The Art of Osamu Tezuka: God of Manga (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2009).

[195] Pellitteri, The Dragon and the Dazzle, 80, 184.

[196] Pellitteri, 80.

[197] Pellitteri, 80.

[198] Shiokawa, 107.

[199] Other notable authors and works of associated with the Year 24 Group include Ōshima Yumiko’s Banana Bread no Pudding (1978) and Wata no Kuni Hoshi (The Star of Cottonland, 1978-87), Yamagishi Ryoko’s Shiroi Heya no Futari (“Couple of the White Room,”1971), or Kihara Toshie’s Angelique (1977).

[200] James Welker, ‘A Brief History of Shonen’ai, Yaoi, and Boys Love’, in Boys Love Manga and Beyond: History, Culture, and Community in Japan, ed. Mark McLelland et al. (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2016), 42–75.

[201] M. J. Johnson, ‘A Brief History of Yaoi’, Sequential Tart, accessed 15 October 2017, http://www.sequentialtart.com/archive/may02/ao_0502_4.shtml.

[202] J. Keith Vincent, ‘Making It Real: Ficiton, Desire, and the Queerness of the Beautiful Fighting Girl’, in Beautiful Fighting Girl (Minneapolis: Univ Of Minnesota Press, 2011).

[203] Shiokawa, ‘Cute but Deadly: Women and Violence in Japanese Comics’, 110.

[204] Shiokawa, 107–12.

[205] Vincent, ‘Making It Real: Ficiton, Desire, and the Queerness of the Beautiful Fighting Girl’, x.

[206] Setsu Shigematsu, ‘Dimensions of Desire: Sex, Fantasy, and Fetish in Japanese Comics’, in Themes and Issues in Asian Cartooning: Cute, Cheap, Mad, and Sexy, ed. John A. Lent (Bowling Green, OH: Popular Press 1, 1999), 130.

[207] Patrick W. Galbraith, ‘Lolicon: The Reality of “Virtual Child Pornography” in Japan’, Image and Narrative : Online Magazine of the Visual Narrative 12, no. 1 (1 March 2011): 102.

[208] Patrick W. Galbraith, The Otaku Encyclopedia: An Insider’s Guide to the Subculture of Cool Japan (Kodansha USA, 2009), 128.

[209] ‘Dimensions of Desire: Sex, Fantasy, and Fetish in Japanese Comics’, 130.

[210] Galbraith, ‘Lolicon’, 102.

[211] Comic Market Committee, ‘What Is the Comic Market?’ (COMIKET, 2014), ‘The 3rd Harumi Era’, https://www.comiket.co.jp/info-a/WhatIsEng201401.pdf.

[212] Murakami, Little Boy, 55.

[213] Foster et al., ‘The Politics of the Signifier II’.

[214] ‘The Cuteness of the Avant‐Garde’, 816.

[215] ‘Introduction: The Time of the Child’, in The Retro-Futurism of Cuteness, ed. Jen Boyle and Wan-Chuan Kao (New York: Punctum Books, 2017), 13.

[216] Kao and Boyle, 14.

[217] Lee Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2004), 3.

[218] Edelman, 2.

[219] ‘“Survival of the Cutest” Proves Darwin Right’, ScienceDaily, 21 January 2010, https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/01/100120093525.htm.

[220] Patrick Barkham, ‘“Kill Them, Kill Them, Kill Them”: The Volunteer Army Plotting to Wipe out Britain’s Grey Squirrels’, The Guardian, 2 June 2017, sec. Environment, http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/jun/02/kill-them-the-volunteer-army-plotting-to-wipe-out-britains-grey-squirrels.

[221] Agence France-Presse, ‘Using Cute Animals in Pop Culture Makes Public Think They’re Not Endangered – Study’, The Guardian, 13 April 2018, sec. Environment, http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/apr/13/using-cute-animals-in-pop-culture-makes-public-think-theyre-not-endangered-study.

[222] ‘Saving or Harming the Planet with Plush Toys?’, Fur Commission USA (blog), accessed 14 June 2018, http://furcommission.com/saving-the-planet-with-plush-toys/.

[223] Harootunian, ‘Japan’s Long Postwar: The Trick of Memory and the Ruse of History’, 119.

[224] Ellis S. Krauss, Thomas P. Rohlen, and Patricia G. Steinhoff, eds., Conflict in Japan (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1984).

[225] Berlant, Cruel Optimism, 24.

[226] ‘The Art of Cute Little Things: Nara Yoshitomo’s Parapolitics’, Mechademia 5, no. 1 (10 November 2010): 29.

[227] Ivy, 5.

[228] Cross, The Cute and the Cool, 44.

[229] Dale et al., The Aesthetics and Affects of Cuteness, 27.

[230] Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories, 2012, 4.

[231] Dale, ‘The Appeal of the Cute Object: Desire, Domestication, and Agency,’ 52.

[232] Anne Allison, ‘The Cultural Politics of Pokemon Capitalism’, 1 January 2002, 2.

[233] Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation by Gilles Deleuze (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2003), 43.

[234] Ngai, ‘Our Aesthetic Categories’, 1 October 2010, 64.A cuter Ph.D.

This dissertation is a collection of essays forming an “encyclopedia” of links between cuteness and negativity in the contemporary milieu, with a focus on the Japanese cute, known as the kawaii. It is also an artist’s book in the form of a website (https://www.heta.moe/) that does not seek to illustrate or explain my artworks but develops their ideas and thought processes through the medium of writing. Because cuteness is “a dumb aesthetic”[1] indexing everything that academic discourse (traditionally) is not, it can conduct certain “acts of sabotage against the academic world and the spirit of system.”[2] As such, cuteness suggests a deviation from traditional dissertation models, valuing attributes opposed to forms of phallogocentrism—namely, the childish, the small, the weak, the playful, the sentimental, the fragmented, the feminine, and so on. In my case, I aim to make my Ph.D. cuter. The choice of form, structure, and themes in my dissertation, therefore, captures the central idea that my artworks and writings world-build together with each other. There is no research question to be dissected, no cutting its internal parts, believing that totality exists even if it is unattainable. Or, rather, if there is a research question, it should be: what can a Ph.D. dissertation do, i.e., what and how can it perform, to reflect my artistic identity? That is, idiosyncratic and constantly changing, sometimes obscure—hopefully—capable of the unexpected; a bit skittish, nervy. Cute (?). The answer, or one possible answer, or the answer I came up with, is that it can serve as a prompt, a stimulus to encourage the creative exploration of everyday objects, to engage with that which enters my mind and my eyes, now and in the future. A reason to really focus my attention (for a short time), and to play with ideas as one does with a ball of string, twisting and untangling.

In other words, I want my Ph.D. dissertation to be like a playing partner, and I want it to go like this: (ノ◕ヮ◕)ノ*:・゚✧. As such, instead of a single question and a single text, I present a collection of short entries relating to kawaii phenomeno-poetics, i.e., one’s experience of the affective, imaginative, and aesthetic meanings exuding from cute objects. I have divided this document into three parts: “Part I – Encyclopedia,” “Part 2 – Three Papers,” and “Part III – Artist’s Statement.” Part I consists of twenty-one shorter entries of 2500 to 4000 words. In entries such as “Absolute Boyfriend,” “Fairies,” or “THE END,” I focus on a single work—respectively, a manga by Watase Yū, the animated television series Jinrui wa Suitai Shimashita, and Shibuya Keiichiro’s video opera THE END—by delving into their thematic, conceptual, and aesthetic substance. Other entries, like “Gesamptcutewerk,” “Pastel Turn,” or “Zombieflat” lack a central object, instead weaving an analysis of various cultural artifacts, connected by an underlying motif, e.g., the “total work of art,” “pastel colors,” and “undeadness.” What all the entries in Part I have in common is my goal of a freer, more speculative scholarship, considering a broad range of objects including mass-cultural artifacts like manga, anime, or videogames, but also painting, sculpture, video art, performance, and so on. On the website, the collection of pictures, GIFs, and videos made à propos of each entry is another crucial component of the encyclopedia. More than an illustration of contents, I wish it to provide a meaningful reflection in and of itself, about the forms of contemporary cuteness.

Part II follows the “three papers” Ph.D. thesis format, a more recent alternative to the traditional dissertation, with a decentralized structure and shorter length. Contrary to the encyclopedia entries in Part I, these papers have about 8000 words and follow the proper format of a humanities research paper, with an abstract, introduction, discussion, and fewer pictures. The three papers presented in this part are “‘Gaijin Mangaka’: The Boundary-violating Impulse of Japanized ‘Art Comic,’” ““Nothing That’s Really There: Hatsune Miku’s Challenge to Anthropocentric Materiality,” and “She’s Not Your Waifu; She’s an Eldritch Abomination: Saya no Uta and Queer Antisociality in Japanese Visual Novels.” The first paper focuses on š! #25 ‘Gaijin Mangaka,’ a special issue of the celebrated pocket-sized comic anthology š! in which I have participated, addressing the question of Japanized contemporary art by Western artists. The second investigates the Japanese virtual idol Hatsune Miku as hyperobject (a concept by philosopher Timothy Morton) from a feminist new materialist perspective. Finally, the third paper delves into Saya no Uta (“Song of Saya”), a Lovecraftian-Cronenbergian adult visual novel, examining it in light of Queer Game Studies and antisocial queer theory. Although on the website, I make no distinction between Part I and II—all entries belong to my imaginary collection of art and pop-cultural objects—these three papers attest to my capacity to navigate different theoretical frameworks and write according to the standard format of academic journals. In fact, at the time of this dissertation’s completion, I have submitted all three articles to international journals with blind peer review. Moreover, “Gaijin Mangaka” relates directly to my artistic “tribe,” i.e., non-Japanese artists using Japanese pop-cultural references in their works, and therefore is suited for a lengthier analysis in the context of this dissertation.

Part III consists of my artist’s statement, my artist’s bio, and my C.V. The artist statement, to be used in my professional practice as an artist, presents an overall vision of my work, situating it in the contemporary art practice. It also directs readers to my online portfolio at https://www.heta.moe/, where I have documented the artworks produced during the duration of my Ph.D., including images, photographs, and short descriptions of each artwork or series of artworks. An abridged version of my online portfolio is also attached to this dissertation. Part III is to be complemented by the final exhibition of my artworks, which will take place at my faculty on the day of the thesis defense.

In the remainder of this introduction, I will detail some aspects concerning my dissertation’s methodology, namely, its “encyclopedic” format. I will also offer a brief observation of the field of Cute Studies and make a general introduction to the question of cuteness and negativity, in which I pre-emptively tackle a set of “negative” concepts which will recur in Parts I and II. After that, I will turn my attention to this dissertation’s main topic, the Japanese cute or the kawaii, addressing its etymology, history, and culture. In the same vein, I present an overview of cuteness and manga—including the Interwar period, girls’ comics (shо̄jo manga) and boys’ comics (shо̄nen manga)—as their coevolution is especially relevant not only to grasp the aesthetics of kawaii but as a primer to various encyclopedia entries. Finally, I will close this introduction with a few concluding remarks (“Coda: Feeling Cute, Might Delete Later”), suggestive of loose ends and future prompts to be explored in relation to cuteness and negativity.

While the dictionary and the encyclopedia are at odds with the Ph.D. dissertation in many ways—for instance, the adjective “encyclopedic” can be used to negatively pass judgment on a thesis, highlighting a propensity for quantity over quality or an excess of the content itself—they are all, at heart, teleological formations. The dissertation culminates in a thesis, in which all parts (literature review, methodology, results) converge towards a theory to be proved, aiming for the specialization of students in one field of knowledge. Even when opening new lines of inquiry in “future work” sections, it entails a sense of closure of a research phase with everything else lying beyond its scope, and Ph.D. students, often suffering from academic fatigue, fantasize about writing the last word in their dissertation’s conclusion. In turn, dictionaries and encyclopedias seek to collect the entirety of knowledge or branch of knowledge. Their alphabetical order is a strategy to organize that which has no inherent ordering, as no word or entry is more important than the other. As such, they are inherently non-sequential, evading the logical chain that characterizes a Ph.D. dissertation.

In the making of this dissertation, I was inspired by a lineage of unconventional “dictionaries” initiated by George Bataille’s critical dictionary in the Documents (1929-30) magazine and continued by Rosalind Krauss and Yve-Alain Bois’s Formless: A User's Guide (1997). [Figures 1 & 2] Both subvert the dictionary as a tool that objectively describes the meaning of words, mocking its aspirations to totality, replaced by a collection of short, idiosyncratic essays. Indeed, Bataille’s dictionary “is not much of one.” As Krauss and Bois put it:

“It is incomplete, not because Bataille stopped editing the magazine at the end of the 1930s, but because it was never thought of as a possible totality (moreover, the articles do not appear in alphabetical order); it is written in several voices (there are three different entries under ‘Eye’ and under ‘Metamorphosis,’ for example); it does not rule out redundancy.”

In Formless, too, the book’s division clashes with its alphabetical order: because all 28 entries are organized from A to Z, the book’s four parts (“Base Materialism,” “Horizontality,” “Pulse,” “Entropy”) seem subject to chance or, at least, conditional to the dictionary’s deterministic order.

Figure 1 Cover of the Georges Bataille’s art magazine Documents No 1, 1929.

Figure 2 Cover of Formless: A User’s Guide by Rosalind Krauss and Yve-Alain Bois, 1997.

My encyclopedia, which is also “not much of one,” uses Bataille’s dictionaries and Formless as models for the dissertation, not just in structure and length, but in their engagement with what Ernest Boyer calls a “scholarship of integration” or “connectedness.”[4] As Boyer writes, “By integration, we mean making connections across disciplines, placing the specialties in larger context, illuminating data in a revealing way, often educating nonspecialists, too.” And continues: “In calling for a scholarship of integration, we do not suggest returning to the ‘gentleman scholar’ of earlier time, nor do we have in mind the dilettante. Rather, what we mean is serious, disciplined work that seeks to interpret, draw together, and bring new insight to bear original research.”[5] To Krauss and Bois, this connectedness is a way “not only to map certain trajectories, or slippages, but in some small way to ‘perform’ them.”[6] In my case, these “trajectories” and “slippages” draw together Western and Japanese objects and frameworks. Indeed, I was first interested in the Japanese cute, the kawaii, because of the way that Japanese comics, animation, and videogames reflect many topics present in Western art and theory in fresh, unexpected ways.

Another crucial feature of dictionaries and encyclopedias is their provisional nature, as language and knowledge are continually shifting and evolving. Ironically, encyclopedias like the online Wikipedia, that incorporate provisionality and open-endness, are often scorned by the gatekeepers of knowledge and referencing them remains, for the most part, an academic no-no. In my encyclopedia, I deliberately insist on the interplay of “high” and “low” sources of information, using books, monographs and papers alongside Tumblr posts and collaborative websites like KnowYourMeme, TvTropes and fan wikis. In doing so, I seek to reflect my experience as a trained scholar and artist who is also a product of the Internet revolution, marked by the rise of user-generated content and social media. Indeed, my interest in the kawaii itself would not have been possible without the unprecedented circulation and accessibility of Japanese popular culture in the 2000s. After all, the millennials were the first generation to be brought up en masse on Japanese cartoons like Dragon Ball, Sailor Moon, Evangelion, or Pokémon, thanks to globalization and the World Wide Web. In the spirit of provisionality, then, an essential aspect of my encyclopedia is that, on my website, it is to remain an open-ended collection of entries, subject to growth and change, of which the volume submitted to my faculty’s administrative services is but a momentary crystallization. After the conclusion of my Ph.D., I will continue to add new entries, and existing entries may be changed or removed, in a continual editing process of which I will keep track in the Blog section of the website.

Figure 3 Cabinet of Curiosities (1695) by Domenico Remps, held in the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, in Florence.

My encyclopedia also employs the archetype of the cabinet of curiosities or wonder-room as an organizing principle, insofar as, like the curiosity cabinet, mine is also a compendium of artifacts. Renaissance wonder-rooms were collections of unusual objects organized in idiosyncratic categories, according to flexible guidelines and the collector’s imagination.[7] [Figure 3] As historian Stephanie Bowry puts it, “Far from being chaotic, cabinets attempted not only to represent, but to actively perform the entangled nature of objects through their selection and categorization of material, and to experiment with the limits of representation by creating new kinds of objects.”[8] The curiosity cabinet exists at the intersection of the encyclopedic and the “weird materialities”[9] of culture, bringing out the entanglement of theory and practice as products of the same world-building drive. What interests me in this model is that, like the dictionary and encyclopedia, the curiosity cabinet is an open-ended collection subject to growth and change, negating the closure expected from Ph.D. dissertations. However, compared to the dictionary and encyclopedia, which tend towards abstraction (i.e., concepts, words, events), the cabinet of curiosities is of an objectual nature. I identify with it more, as each of my entries originates from looking at an object, artwork, or character, and mapping its connections to other artifacts and concepts. In a sense, in building my encyclopedia, I, too, feel like I am a collector of sorts, adding my treasures to an imaginary (virtual) room.

Figure 4 Example of a “Wacky Orientalism” in the website The Travel, October 15, 2018.

The cute and the curious also share some common ground as aesthetic categories. On the one hand, the curious bears a suggestion of smallness, as it is often not surprising or impressive enough to be “astonishing” or “amazing,” thus hinting at a passing interest in things sufficiently tiny to fit into a cabinet. On the other, despite its strong influence in contemporary culture, cuteness remains, for the most part, a “curiosity” in aesthetic criticism, resisting the solemnity of established categories like the beautiful or sublime.[10] Exotic Japan, too, has always been a cabinetizable curiosity in the eyes of the West, reduced to the decorative motif of Japonaiserie, i.e., the porcelain, lacquerware, and screens eagerly sought after by seventieth-century collectors and onward.[11] Even today, kawaii culture fits neatly into the discourse of “wacky orientalism,”[12] with lists of Japan’s most disturbing prefecture mascots (yuru kyara) amusing the Internet alongside news of Hello Kitty dildos and insane street fashion like gyaru (“gal”) or decora. [Figure 4] For better or worse, these stereotypical associations of “Japaneseness” hold a poetic significance in their transgression of the boundaries of nature and artifice, reality and fantasy, encouraging the formulation of playful connections between objects, concepts, and affects.

Moreover, while the Portfolio and the Encyclopedia exist in separate sections on my website, the homepage is a section exhibiting the writings and the artworks mixed in with each other: the GRL KABINETT. Here, encyclopedia entries and portfolio entries are represented by AI-generated anime girls, created by using the website https://make.girls.moe, and curated from a pool of several hundreds of automatically generated girls to best fit the spirit of each entry. In animanga fandom, this process is called moé anthropomorphism, or moé gijinka, in Japanese, “a form of anthropomorphism in anime and manga where moé qualities are given to non-human beings, objects, concepts, or phenomena.”[13] In moé anthropomorphism, “Part of the humor of this personification comes from the personality ascribed to the character (often satirical) and the sheer arbitrariness of characterizing a variety of machines, objects, and even physical places as cute.”[14] Because the girls are unlabelled, accessing the entries from the GRL KABINETT also encourages visitors to engage playfully—and, perhaps, a bit annoyingly!—with the contents of my website.

Figure 5 A glass display containing anime figures, in the room of an otaku.

The choice to represent the curiosities in this virtual cabinet through moé anthropomorphism, instead of icons retaining a mimetic relationship to their content, hints at the contradictions of cute aesthetics in contemporary culture, namely, at cuteness’s permanent tension between reinforcing and subverting the existing social order, sometimes, in the same gesture. Indeed, as scholar Thomas Lamarre puts it, “unless you’ve mastered easy flight to other planets, you’ve surely run up against signs of increasing anxiety about the effects of capitalism in today’s world… Regardless of what you think about capitalism, it’s hard to escape a sense of disparity between the creativity of consumer activity today… and the contemporary crisis of capitalism.”[15] I find this contrast both funny and unsettling in ways that reflect, quite efficiently, the contradictions in my own writings and artworks. After all, what does it mean to thread so intimately among the products of consumer culture? Regardless of analytical depth, in the end, what will my wonder-room look like? Perhaps not so much like a cabinet of curiosities, but like the figurine-encasing displays in the rooms of an otaku?

In embracing the relational quality of the curiosity cabinet, I do not rely on a hard definition of cuteness. Instead, my premise is that “cuteness itself is defined in relative terms, based on the available elements in each story,”[16] each chapter, each entry. This indeterminism aligns with the belief that, as scholar Joshua Dale argues, cuteness is “a potential… response to a definable (albeit not completely defined) set of stimuli,”[17] and therefore an overarching, ossified definition would cut against the methodological grain of my encyclopedia. This “case by case” approach, based on close reading and close looking, facilitates the temporal and geographical transitions arising throughout my encyclopedia, as I impose no time or space restrictions on the analyzed objects. But also, it allows me to explore cuteness in terms of content and representation through different theoretical frameworks, drawing from an array of knowledge fields including art studies, critical theory, Japanese studies, anime and manga studies, comics studies, media studies, queer studies, gender studies, feminist theory, new materialism, and so on. I also assume a stance in which no object is undeserving of detailed attention, regardless of its smallness. In fact, in my experience and art practice alike, it is often from details and the more fleeting sensations that words and images are fleshed out, rather than from totalizing thought systems.

Finally, in examining the relationship between cuteness and negativity, I have made a deliberate effort to include art and pop culture that is not only Japanese but also Japanized—what scholar Casey Brienza has called Japanese pop culture “without Japan,”[18] meaning “products of a sometimes globalized, sometimes transnational, sometimes hyperlocal world… produced without any direct creative input at all from Japan”[19] but which nevertheless retain symbolic and stylistic markers associated with manga, anime, Japanese videogames, and so on. Yoda Tomiko, too, has argued that the handle “J-” often accompanying the products of Japanese pop culture (e.g., J-pop) is useful precisely because of its degree of separableness from the national. As a part-object, “J-” embodies the contractions and contradictions of “Japan” (or any nation-state, really) in globalized capitalism. As she puts it, “Rather than assuming that the Japanese popular culture today ultimately refers to some form of larger national frame, we may understand the prefix J- as inscribing the subculturation of the national.”[20] In Introducing Japanese Popular Culture (2011), scholars Alisa Freedman and Toby Slade indorse a similar view (with which I concur), writing that,

At the heart of any definition of Japanese popular culture are a number of contradictions. First, we believe that the use of a nation-state, such as Japan, as an organizing principle for the categorization of culture, especially contemporary popular culture, is ultimately untenable. We see Japanese popular culture as a study of information flows associated with Japan rather than anything “essentially” or “authentically” Japanese. In the case of Japan, this is sometimes less arbitrary because of the barriers of geography and language. Thus we demonstrate that the designation “Japanese” in Japanese popular culture is more an associative starting point than a marker of exclusivity or locus of origin for what are indeed a globalized set of phenomena.[21]

By expanding the objects of analysis to outside the boundaries of Japan’s territory (a particularly enclosed one, considering its insular position), I wish to emphasize that these essays are meant to reach a broader crowd beyond the niche of animanga[22] fans and fellow weeaboos (“wapanese” or “wannabe Japanese,” obsessive Western fans of anime and manga). Presently, Japanese popular culture is an unavoidable “soft power,” which seeps into our everyday lives, and whose influence makes itself more and more visible in non-Japanese art schools and contemporary art. For instance, as the encyclopedia entry and paper “Gaijin Mangaka” addresses, in the 2020s, the realm of experimental graphic narratives, called “art comics,” has experienced a wave of non-Japanese authors openly influenced by manga. Likewise, references to Japanese popular culture, particularly comics and animation, have become a not uncommon occurrence in Western contemporary art, especially in the work of artists currently in their 20s and 30s. Sometimes, these can cause educators and students to clash and struggle, either to understand and accommodate these trends within their viewpoints (in the former’s case) or to present and navigate their preferences within a contemporary art world context (in the latter’s). I hope that my encyclopedia contributes, at some level, to a better understanding that kawaii, anime, and manga operate beyond the boundaries of subcultures or the Japanese nation-state and, therefore, can be productively used to engage with all kinds of art and aesthetic criticism, including in educational contexts.

Figure 6 Cover of Sianne Ngai’s Our Aesthetic Categories: Cute, Zany, Interesting, 2012.

As an emerging academic field, Cute Studies or Cuteness Studies encompasses interdisciplinary scholarship from the natural sciences, the social sciences, and the humanities.[23] The term was coined by scholar Joshua Dale, who has promoted its development and dissemination by launching the online resource Cute Studies Bibliography, co-editing The Aesthetics and Affects of Cuteness, and editing the “Cute Studies” special edition of the East Asian Journal of Popular Culture, both in 2016. To date, other cute-centric academic publications include an issue on Internet cute by the M/C Journal (2014) and The Retro-Futurism of Cuteness (2017), edited by Jen Boyle and Wan-Chuan Kao. The study of cute aesthetics in Western scholarship was pioneered in the 1990s and 2000s by cultural theorist such as Daniel Harris (Cute, Quaint, Hungry and Romantic: The Aesthetics of Consumerism, released in 2000) and Sianne Ngai (starting with “The Cuteness of the Avant‐Garde” in 2005), along with Sharon Kinsella, a sociologist specializing in kawaii, and Garry Cross, who wrote the landmark history of American cute culture The Cute and the Cool: Wondrous Innocence and Modern American Children's Culture, in 2004. Ngai’s scholarship of cuteness culminated in Our Aesthetic Categories: Cute, Zany, Interesting (2012), [Figure 6] in which she argues that cuteness reveals “the surprisingly wide specter of feelings, ranging from tenderness to aggression, that we harbor toward ostensibly subordinate and unthreatening commodities.”[24]

Ngai’s integration of cuteness within her broader project of examining the “politically ambiguous work of… emotions”[25] contributed to establishing cute aesthetics as a valid topic of research. Ngai’s “The Cuteness of the Avant-Garde” (2005), her earliest article on cuteness later adapted into a chapter in Our Aesthetic Categories, focuses on Japanese contemporary artists like Murakami Takashi and Nara Yoshitomo[26] as hallmarks of cuteness’s dark side. In turn, Sharon Kinsella has published several key books and articles on Japanese cuteness and girls’ culture, including the 1995 article “Cuties in Japan”—which remains a reference in many texts on kawaii aesthetics—along with Adult Manga: Culture and power in contemporary Japanese society (2000), Female Revolt in Male Cultural Imagination in Contemporary Japan (2007), and Schoolgirls, Money and Rebellion in Japan (2013). Additionally, in 2010, anthropologist Marilyn Ivy penned “The Art of Cute Little Things: Nara Yoshitomo's Parapolitics,” published in the fifth volume of the animanga-centric academic journal Mechademia, an important paper examining the political significance of Japanese artist Nara Yoshitomo in light of kawaii aesthetics. Since then, during the span of the 2010s, there has been a general increase in papers focusing on Japanese cuteness, hailing from various academic fields.

Figure 7 Cover of The Aesthetics and Affects of Cuteness, 2016.

In the second half of the 2020s, a notable contribution to the field of Cute Studies was the edited volume The Aesthetics and Affects of Cuteness, published by Routledge in 2016, edited by Dale, Joyce Goggin, Julia Leyda, Anthony McIntyre, and Diane Negra. [Figure 7] This collection of essays offers a comprehensive view on the “explosion of cute commodities, characters, foods, fashions, and fandoms, leading to an inevitable expansion and dispersal of meanings and connotations”[27] in the twenty-first century. The authors put forth an understanding of cute affects, cultures, and aesthetics as “a repertoire that is made use of by a variety of constituencies and for a variety of purposes.”[28] The book breaks down the appeal of cute aesthetics in several elements: cuteness, coping, labour; cute consumption, nostalgia, and adulthood; cute communities and shifting gender configurations; cute compassion and communication; cute encounters: anthropomorphism and animals; spreadable cuteness: interspecies affect; political cuteness; cuteness and/as manipulation.[29] Dale, in particular, importantly argues that cuteness is fundamentally “aimed at disarming aggression and promoting sociality,”[30] and that “antagonistic qualities such as violence, aggression, and sadism are not intrinsic to the concept of cuteness” but “are frequently attached to cute objects in the aesthetic realm.”[31] Although, for instance, Ngai’s analyses of the aggressive impulses aroused by the cute object are firmly rooted in psychoanalytic theory and ethnographic observation—and, therefore, contrary to what Dale’s argument may suggest, not a detached fabrication of the artistic sphere—Dale’s case nevertheless cautions us against the hasty association of cuteness with “darkness.”

Figure 8 Konrad Lorenz’s kinderschema (“baby schema”) porportions: neonates on the left, adults on the right.

Figure 9 Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Les Hasards heureux de l'escarpolette (“The Happy Accidents of the Swing”), 1767. Oil on canvas, 81 cm × 64.2 cm.

Before advancing, one may raise the question: what is cuteness? Cuteness can be understood on two different, if necessarily interconnected, levels. On the one hand, from a psychophysiological point of view, cuteness is an “affective response—a feeling one may refer to as the ‘Aww’ factor”[32] serving as an evolutionarily advantageous trait. This “natural” cuteness, understood as a primal, protective instinct towards neonates, is also not exclusive to humans, intertwining with the broader evolution of animals on Earth. In the 1940s, Austrian ethologist Konrad Lorenz was the first to describe what he called kinderschema, or “baby schema,” a set of features and behaviors found in animals, including humans, indexing youthfulness and vulnerability, that trigger our nurturing instinct. [Figure 8] Lorenz’s kinderschema included big eyes positioned low in large heads with tall foreheads, a small mouth and nose, round ears, small chin, soft limbs and body, and a waddling gait. The Aww-factor can impact biological capacities; for instance, a recent study suggests that the millennial-long coevolution of dogs and humans has resulted in the latter developing a forehead muscle to produce the proverbial puppy dog eyes, i.e., a sad, imploring, juvenile expression.[33] Nevertheless, many scientists today argue that “instead of stemming solely from helplessness and dependence, cuteness is… intimately linked to companionship, cooperation, play, and emotional reactivity,”[34] suggesting it plays a role in motivating prosocial behavior, empathy, and disarming aggression.[35]

On the other hand, cuteness exists as a socio-cultural concept and, by extension, as an aesthetic category. This “second nature” of cuteness is relatively recent in human history, relating to the word’s emergence at the dawn of the twentieth century—although its roots can be traced back further, for instance, to Rococo’s fascination with the small and playful against Baroque's grandeur, encapsulated in works like Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s L'Escarpolette, [Figure 9] or some Edo period paintings and prints in Japan.[36] According to historian Gary Cross,

“Until the twentieth century, “cute” was merely a shortened form of “acute,” signifying “sharp, quick witted” and shrewd in an “underhanded manner.” In American slang of 1834, it came also to mean “attractive, pretty, charming” but was applied only to things. The original meaning of the “cute” person was interchangeable with “cunning,” a corruption of “can,” meaning cleaver or crafty. Significantly, both words shifted meaning by the 1900s (though only briefly for cunning), from the manipulative and devious adult to the lively charm of the willful child, suggesting anew tolerance for the headstrong, even manipulative youngster. Today, the little girl who bats her eyes to win favor or the little boy who gives his mother a long look of desire at the candy counter is called “cute.””

Figure 10 Sianne Ngai’s illustration of cuteness’s propensity for deformation in “The Cuteness of the Avant-Garde,” 2005.

Thus, as Sianne Ngai suggests, the word “cute exemplifies a situation in which making a word smaller, more compact, or more cute results in an uncanny reversal, changing its meaning into its exact opposite.”[38] Here, the cute indexes various meanings, including that which is attractive by means of smallness prettiness, or quaintness. In this sense, cuteness evokes the “toy-like or pet-like,”[39] tameness aligned with the limiting of the physical, formal, and philosophical scope of objects. For instance, the small is that whose size is less than average, and this “less than” or “lack” evokes another set of features that Ngai lists as “compactness, formal simplicity, softness or pliancy.”[40] [Figure 10] In fact, the kinderschema are, in and of themselves, a kind of “deformity” or “distortion” in relation to the “standard,” i.e., the adult, connoting immaturity, innocence, and dependence. On the other hand, the pretty is a “desintensification” or domestication of the beautiful, something which is appealing in a delicate and graceful way but removed from the solemnity of beauty as a central category in classical art—one could argue that the pretty is a cutification of the beautiful. In turn, the quaint “declaws” strangeness into that which is quirky, i.e., unusual or idiosyncratic in non-threatening, often adorable, sometimes, old-fashioned, ways.

Moreover, and albeit in an entirely different context (referring to sound), Bradon LaBelle’s account of weakness as, potentially, a euphoric and erotic (in the sense of a life-inducing impulse) condition, which “reveals us at our most vulnerable, a body without and in need,”[41] echoes Ngai’s definition of cuteness as “an aesthetization of powerlessness,”[42] i.e., as the depiction of “helplessness, pitifulness, and even despondency”[43] as artistically or sensually pleasing, in ways that evoke our tender love and care. In this light, one can think of the cute as an intersection where the life instinct to nurture, protect, an love meets the minor, insignificant body and object. This structural disenfranchisement applies to the category of cuteness itself in relation to the Western art canon, as “a minor aesthetic concept that is fundamentally about minorness.”[44]

Figure 11a Icons of mass-market art: Giovanni Bragolin’s Crying Boys.

Figure 11b Icons of mass-market art: Margaret Keane’s big-eyed paintings.

Cross also suggests that cuteness can “weaponize” these features as charm contrived with a view to desired ends. Here, the cute becomes entangled with sentimentality and the self-indulgent appeal to tenderness and nostalgia. The iconic Crying Boys painting series by Italian painter Giovanni Bragolin, an icon of kitsch mass-market art, epitomizes this relationship, but it could also refer to Margaret Keane’s paintings of big-eyed women and children, or the kitty and puppy calendars hanging in homes all over the world. [Figure 11a, b] These associations have put cute aesthetics squarely on the “dumb” side of what art and literary critic Andreas Huyssen famously called “the Great Divide”[45] between “high art” and lowly mass culture, a contested conceptual trope emerging in nineteenth-century Europe that has nevertheless proved to be amazingly resilient throughout the twentieth century.[46] Indeed, Cross argues that cuteness is intimately related to the birth of consumer culture, as it became “a selling point (especially when associated with the child in ads) and an occasion for impulse spending”[47] in emerging child-oriented festivities like Christmas, Halloween, and birthday parties. These were the beginnings of the cute as a commodity form, which over the twentieth and twenty-first century grew to enormous proportions, to the point that it has been called a “cuteness-industrial complex.”[48] The idea that, as argued by Ngai, cuteness has become one of “capitalism’s most binding processes,”[49] and therefore is no longer “merely” an aesthetic but an authoritative economic interest and value system, allied with the consumer goods sector, is essential throughout my dissertation, especially in regards to the development of the kawaii in Japanese society. It is at the core of all sorts of negativity and ambiguities spiraling from the cute commodity.

Figure 12 Kellogg’s advertisement featuring an adorably selfish little girl, 1911.

Figure 13 Color plate by Frank Reynolds in an illustrated edition of David Copperfield, 1911, showing David, Dora, and her lapdog, Jip.

Cuteness is also the fruit of modern psychology, replacing the passive Victorian child with mischievous rascal boys or cheeky coquette girls.[50] The fact that “children were no longer imagined as miniature adults or as naturally virtuous creatures”[51] resulted in a sociocultural shift that not only tolerated but encouraged them to express emotions and behaviors that would be considered antisocial in adults.[52] [Figure 12] Cross illustrates this uncanny, dual constructive and destructive nature of cuteness with examples of late nineteenth-century American trade cards, in which children using a sewing machine to stitch together the tails of cats and dogs, or getting hit in the face with a baseball ball,[53] are shown to be cute. But one could just as easily fetch the example of literary heroines like Charles Dickens’s Dora Spenlow in David Copperfield (1850). David Copperfield’s first wife, Dora, is described as “pretty,” “little” (“little voice,” “little laugh,” “little ways”), “rather diminutive altogether,” and “childish.” She baby talks and throws tantrums, and is always accompanied by her spunky lapdog, Jip. [Figure 13] Although commonly understood as an “empty-headed child,”[54] Dora is self-aware and even tells David that he should think of her as his “child-wife” (e.g., “When you are going to be angry with me, say to yourself, ‘it’s only my child-wife!’ When I am very disappointing, say, ‘I knew, a long time ago, that she would make but a child-wife!’”). By acting childish and vulnerable, Dora—much like the practitioners of Japanese fashion and subcultures related to the kawaii—evades the responsibilities of married life and enfolds David in “a playful, unserious anarchic moment”[55] which is ultimately unsustainable in family literature (Dora, therefore, dies shortly into their marriage). Characters like Dora portray a budding admiration for the “slightly manipulative and self-centered girl”[56] in nineteenth-century urban society. Likewise, Little Nemo, Felix the Cat, Krazy Kat, Mickey Mouse, or Betty Boop, embody the moral and aesthetical ambiguity, even disruptiveness, of cuteness in early comics and cartoons, initially targeted not at children but an adult audience, imbued with a modern sensibility. As Dale puts it, “when Mickey Mouse debuted in the animated cartoon Steamboat Willie (1928) he was mischievous to the point of cruelty.”[57] [Video 1]

Video 1 The official debut of Mickey and Minnie Mouse in the short animated film Steamboat Willie, directed by Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks in 1928.

Figure 14 Garrus from Bioware’s popular videograme series Mass Effect.

Figure 15 The blobfish, “the world’s ugliest animal.”

Disconnected from the biodeterminism of Konrad Lorenz’s kinderschema, the “minorness” of cuteness performs in ways which are fundamentally contingent and relational. This is not to say that everything is (or can be) cute—as I have discussed above, cuteness evokes a word cloud or arena in which “diminutive,” “negative,” or “formless” attributes combine with benign qualities: small, weak, helpless, pitiful, dumb, manipulative, young, pretty, quaint, playful, tame, adorable, and so on. But in the artistic and pop-cultural realm, cuteness often reflects the fact that “social and subcultural groups have their own (rather specific) criteria for what sorts of manners and attitudes constitute ‘cute.’”[58] For instance, the character of Garrus from the video game series Mass Effect, who is an anthropomorphic alien with insectoid features, is a favorite among the female gamer community for his cute awkwardness and vulnerability.[59] [Figure 14] Likewise, while relying on an aesthetics of precarity and imperfection which is far from being “conventionally” cute (attractive, pretty, etc.), many artworks produced within the trend of provisional painting might be considered “cute” in defying the aesthetic grandeur traditionally expected from artworks. Even the ugly can be cute, to some extent: the World’s Ugliest Dog Contest is an example of such concoction of cuteness and ugliness, or the blobfish, voted the world’s ugliest animal in 2013 by the Ugly Animal Preservation Society,[60] [Figure 15] or even the cutification of disability in Internet celebrity cats like the late Grumpy Cat or Lil Bub.[61] Indeed, according to scholar Kanako Shiokawa, the non-descriptiveness of cuteness is central to cuteness’s contemporary acceptation.[62] In many respect, the kawaii, i.e., the Japanese cute, is particularly elastic, and a fertile ground for investigating the phenomeno-poetics of cuteness and negativity—what Joshua Dale calls the “dark side of cute.” As Dale puts it,

“The rapid expansion of kawaii since the 1970s has resulted in repeated iterations and cycles that I argue make kawaii more complex and varied than other aesthetics of cuteness... This decade‑long expansion has seen many antagonistic elements attached to kawaii, resulting in substantial trends in Japan for ugly-cute, grotesque‑cute, and disgusting‑cute, to name a few.”

In art and popular culture, cuteness is entangled with a variety of other aesthetic categories and concepts, such as the abject, the formless, the uncanny, the eerie, the weird, the obscene, the grotesque, or the disgusting, with their own history and range. These share a “trajectory towards negation”[64] and alterity that aligns them more than separates them, prompting many overlaps. Abjection is a crucial concept in art theory, and one that underlines and manifests in many (if not all) of the enclyclopedia entries and papers in this dissertation—albeit in radically different ways, from the eruption of cuteness in the Dark Web to the internalized foreigness of global manga, or the nonhumanity (the otherness) of cute characters and people. The word “abjection” comes from the Latin abicio, meaning “throw or hurl down or away, cast or push away or aside,” “give up, abandon; expose; discard,” or “humble, degrade, reduce, lower, cast down.”[65] At its most fundamental, the abject signals “the otherness in us,”[66] permeating both our mental processes and the social-cultural order.[67] Julia Kristeva’s 1980 Pouvoirs de l'horreur. Essai Sur l'Abjection (in English, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection) remains the definitive theory of abjection; but there have been many significant contributions to its study, such as Hal Foster’s essay “Obscene, Abject, Traumatic,” published in the art journal October in 1996.

Bodily waste like urine, feces, and other “excretions” (in the sense of substances excreted from our bodies) like blood, semen, or breast milk, are prototypically abject. But the concept also refers to marginalized persons or groups that deviate from the norms of a society at a given moment in space or time, based on their appearance (gender, age, race, ethnicity, disabilities) or living standards (sexual orientation, class, religion, legal status). The duality creates a tension between the “abject” as a noun and “to abject” as a verb. According to scholar Rina Arya, author of Abjection and Representation: An Exploration of Abjection in the Visual Arts, Film and Literature, “While the operation (of abjection) seeks to stabilize, the condition (of the abject) is inherently disruptive, meaning that there is a constant tension of drives.” And continues: “The concept is both constructive (in the formation of identities and relationship to the world) and destructive (in what it does to the subject).”[68] The abject is therefore disruptive and unassimilable, threatening the stability of individual, social, and moral boundaries, as it undoes the distinction between the Self and Other.

Moreover, “the operation of abject-ing involves rituals of purity that bring about social stability,”[69] applying not just to bodies or social groups but also to art. For instance, “high culture” gatekeeps artistic purity by abjecting the “others” of taste and originality, like the kitsch or the plagiarized. Ngai argues that cuteness is abject in relation to the avant-garde, representing its greatest fear: powerlessness, “its smallness (of audience as well as membership), incompleteness (the gap between stated intentions and actual effects), and vulnerability (to institutional ossification).”[70] Still, according to her, the real power of both the cute object and of art itself ultimately resides in its powerlessness. In other words, the insistence on its radical uselessness is the condition sine qua non for the emergence of the avant-garde.

Figure 16 Example of the big eyes in a shōjo manga by Nishitani Yoshiko, from the 1969s.

The extent to which the formless and the abject intersect has been the subject of debate. In 1994, the arts journal October published “The Politics of the Signifier II: A Conversation on the ‘Informe’ and the ‘Abject’” by Hal Foster, Benjamin Buchloh, Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, Denis Hollier, and Helen Molesworth,[71] a roundtable on the formless and the abject, discussing their differences and similarities. Krauss points out how the abject is often reified into “a thematics of essences and substances,”[72] while the formless resists reification and therefore cannot be signified. Arguably, this interpretation of abjection is reductionistic—for Kristeva, the abject draws us “toward the place where meaning collapses,”[73] which aligns with Bataille’s declaration that “What it [the informe]designates has no rights in any sense and gets itself squashed everywhere, like a spider or an earthworm.”[74] Still, one may trace a distinction of emphasis between the abject and the formless; the former, drawing from Kristeva's reading of Freudian and Lacanian psychoanalysis, emphasizes the in-betweenness of I and not-I, while the latter emphasizes the no-thing, the “matter at the thresholds of its annihilation and disappearance” [75] inferred through its effects on outside observers. While the ties of cuteness to the formless are less obvious, I suggest it can be traced, for instance, in the “gleams and reflections”[76] of the big eyes of Japanese girls’ comics, whose wet and sparkly masses, enclosed by long lashes akin to a Bataillean spider, defunctionalize the eye as an organ of the visual system. [Figure 16]

Figure 17 The cute “paradog” turns eerie in the anime series Jinrui Wa Suitashimashita, 2011.

There is a cluster of concepts that orbit the abject (or the other way around), namely, the unheimlich, as immortalized in Freud’s 1919 essay. Meaning “unhomely” in German, the unheimlich indexes an intimate alienation, which “can take the form of something familiar unexpectedly arising in a strange and unfamiliar context, or something strange and unfamiliar unexpectedly arising in a familiar context.”[77] The unheimlich connects with Lacan’s “extimacy” (extimité), i.e., “intimate exteriority,”[78] which is not contrary to intimacy but instead posits that “that the intimate is Other—like a foreign body, a parasite.”[79] In the posthumous The Weird and the Eerie (2017), Mark Fisher argues that, because “Freud’s unheimlich is about the strange within the familiar, the strangely familiar, the familiar as strange,”[80] it is unreconcilable with related concepts, such as the weird and the eerie, that rely on that which “does not belong.”[81] Or, in the case of the eerie, that catches the human “in the rhythms, pulsions and patternings of non-human forces,”[82] an idea whose possible intersection with the cute I explore in the encyclopedia entry “Paradog.” [Figure 17]

Video 2 “PARO is a therapeutic robot modeled on a baby harp seal, developed by the AIST and available from Intelligent System Co., Ltd.

The concept of unheimlich was famously used by Japanese robotics professor Mori Masahiro to describe the uncanny valley (bukimi no tani), a hypostasized “shift from empathy to revulsion” as a humanlike robot “approached, but failed to attain, a lifelike appearance.”[83] As Dale points out, domestication is a crucial element in cuteness, and therefore the cute is always, in one way or another, about the tame and familiar, even when artists negate or subvert these qualities to an “unhomely” effect. The realization that such unsettling feelings do not necessarily detract from the “Aww-factor” further complexifies the interplay of the cute and the uncanny. For instance, the Japanese therapeutic baby seal robot Paro, designed to calm patients and treat depression at hospitals and nursing homes,[84] is quintessentially cute but also carries unsettling qualities—both in the mechanical-automaticness of its movements and utterances, and the ethical implications of replacing “real” human or animal love with a robotic “illusion of a relationship.”[85]

Figure 18 Mukikawa idols: Saiki Reika (left) and Ladybeard (right).

Figure 19 Example of a Lisa Frank illustration with a kitty-angel, rainbow, hearts, and butterflies.