C

CREEPYPASTA

[1] Austin Considine, “Creepypasta, or Internet Scares, If You’re Bored at Work,” The New York Times, November 12, 2010, para. 5.

[2] Considine, para. 11.

[3] “What Is Creepypasta?,” Creepypasta Wiki, paras. 3-5, accessed April 29, 2018.

[4] Jussi Parikka, “New Materialism as Media Theory: Medianatures and Dirty Matter,” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 9, no. 1 (March 2012): 99.

[5] melaphyre, “Creepypasta,” DeviantArt, accessed April 29, 2018.

[6] “Momo Challenge,” Know Your Meme, accessed June 1, 2019.

[7] Alex Martin, “Japanese Artist behind Ghastly Creature in Viral ‘Momo Challenge’ Baffled by Disturbing Hoax,” The Japan Times Online, March 6, 2019, para. 6.

[8] “Momo Challenge,” “Wholesome Momo.”

[9] Olivia Rose Marcus and Merrill Singer, “Loving Ebola-Chan: Internet Memes in an Epidemic,” Media, Culture & Society 39, no. 3 (April 1, 2017): 341.

[10] “Ebola-Chan,” Know Your Meme, 2015, “Origin,” para. 1.

[11] “Ebola-Chan,” para. 2.

[12] “Ebola-Chan,” para. 5.

[13] “Winter-Chan,” Know Your Meme, 2016, “Origin” para. 1.

[14] “Video Games,” Creepypasta Wiki, accessed April 30, 2018.

[15] According to the Creepypasta Wiki, “BEN Drowned, or Haunted Majora's Mask, is a well-known creepypasta (and later, an alternate reality game) created by Alex Hall, also known as ‘Jadusable.’ The story revolves around a Majora's Mask cartridge that is haunted by the ghost (if it is a ghost) of a boy named Ben” (“BEN Drowned,” Creepypasta Wiki, accessed April 30, 2018.)

[16] According to the Creepypasta Wiki, “Majora's Mask is a Legend of Zelda creepypasta about hacking a used copy of Majora's Mask with a GameShark” (“Majora’s Mask,” Creepypasta Wiki, accessed April 30, 2018)

[17] According to the Creepypasta Wiki, “The Lavender Town Syndrome (also known as ‘Lavender Town Tone? or ‘Lavender Town Suicides’) was a peak in suicides and illness of children between the ages of 7-12 shortly after the release of Pokémon Red and Green in Japan… Rumors say that these suicides and illness only occurred after the children playing the game reached Lavender Town, whose theme music had extremely high frequencies, that studies showed that only children and young teens can hear, since their ears are more sensitive. Due to the Lavender Tone, at least two-hundred children supposedly committed suicide, and many more developed illnesses and afflictions… After the Lavender Tone incident, the programmers had fixed Lavender Town’s theme music to be at a lower frequency, and since then children were no longer affected by it. (“Lavender Town Syndrome,” Creepypasta Wiki, accessed April 30, 2018)

[18] “Dennō Senshi Porygon,” in Wikipedia, July 10, 2018, para. 2.

[19] “Dennō Senshi Porygon,” “Aftermath” para. 3.

[20] Griffin Andrew, “Pokemon Go: Don’t Try and Catch Creatures in the Fukushima Disaster Zone, Trainers Told,” The Independent, July 27, 2016, online edition, sec. Gaming; Alexandra Klausner, “You Can Play Pokémon Go in Radioactive Chernobyl,” December 15, 2016, online edition, sec. Living.

[21] Germán Sierra, “Filth as Non-Technology,” KEEP IT DIRTY a. (2016): 5.

[22] Associated Press, “Hiroshima Unhappy Atomic-Bomb Park Is ‘Pokemon Go’ Site,” Naples Herald (blog), July 27, 2016; Allana Akhtar, “Holocaust Museum, Auschwitz Want Pokémon Go Hunts Out,” USA Today, July 12, 2016; Russell Holly, “Please Stop Playing Pokémon Go in Cemeteries,” Android Central, July 29, 2017.

[23] Matthew Loffhagen, “The 15 Worst Real World Dangers of Playing Pokémon GO,” Screen Rant, July 12, 2016, “Injuries” para. 1.

[24] Harry Cockburn, “Two Men Walk off Cliff While Playing Pokemon Go,” The Independent, July 14, 2016, paras. 1-2.

[25] Amalthea, “Pokemon Go Put Me in the ER Last Night,” reddit, July 7, 2016, para. 1.

[26] Andrew Campbell, “Pokemon Go and Moral Panic,” Looking Up (blog), August 2, 2016; Loffhagen, “The 15 Worst Real World Dangers of Playing Pokémon GO.”

[27] Dave Smith, “Hundreds of People Mobbed Central Park to Catch a Vaporeon in Pokémon GO,” Business Insider, July 17, 2016.

[28] Ben Gilbert, “This 40-Second Video Will Convince You That ‘Pokémon GO’ Is an Insane Phenomenon,” Business Insider, July 15, 2016.

[29] Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), 5.

[30] Omari Akil, “Warning: Pokemon GO Is a Death Sentence If You Are a Black Man,” Medium (blog), July 7, 2016, paras. 8-13.

[31] Lynzee Loveridge, “Couple Who Met via Pokémon GO Receive Ultimate Wedding Video,” Anime News Network, November 16, 2018.

[32] MrBijomaru, “R/Pokemongo - How Pokémon GO Saved Me [Discussion],” reddit, accessed June 1, 2019.

[33] Takahiro A. Kato et al., “Can Pokémon GO Rescue Shut-Ins (Hikikomori) from Their Isolated World?,” Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 71, no. 1 (n.d.): 75–76.

[34] Ying Xian et al., “An Initial Evaluation of the Impact of Pokémon GO on Physical Activity,” Journal of the American Heart Association: Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Disease 6, no. 5 (May 16, 2017).

[35] Hashtags such as “beheading,” “skull fuck,” “eye fuck,” “brain fuck,” “hanging,” “amputation.” “impalement,” “broken neck,” “petrification,” “necrophilia,” “electrocution,” “evisceration,” “cut in half,” “strangulation,” “taxidermy,” or “crushed head,” are but a small sample of the materials which can be found on the website.

[36] Miriam Silverberg, Erotic Grotesque Nonsense: The Mass Culture of Japanese Modern Times (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 28–30.

[37] Raisin-In-The-Rum, “Gurochan’s Onion Url While ‘Gurochan.Ch’ Is down Answers,” Discussion Group of Blog Posting, Reddit, May 29, 2017.

[38] “Gurochan,” in Encyclopedia Dramatica, accessed January 23, 2017.

[39] Fred Botting, “Dark Materialism,” Backdoor Broadcasting Company (blog), 2011, para. 1.

[40] Aurel Kolnai, On Disgust, ed. Barry Smith and Carolyn Korsmeyer (Chicago: Open Court, 2003), 30.

[41] Aurel Kolnai put forth this idea in the first comprehensive study on the phenomenology of disgust, Der Ekel (“On Disgust”), in 1929.

[42] Sierra, “Filth as Non-Technology,” 2.

[43] “On The Origins of The Cute as a Dominant Aesthetic Category in Digital Culture,” in Putting Knowledge to Work and Letting Information Play, ed. Timothy W. Luke and Jeremy Hunsinger, Transdisciplinary Studies 4 (SensePublishers, 2012), 219.Creepypasta is an Internet slang term for short horror stories, urban legends, or images propagated on the Internet via chain emails, message boards, and social media with the intent of causing web scares.[1] “Creepypasta” is a derogatory wordplay on “copypasta,” a term coined by the 4chan community for forum posts copy-pasted from memes, old forum posts, or other materials.[2] Old-school creepypasta is usually brief, consisting of scary anecdotes and tales, instructions for performing rituals, or macabre “lost episodes” of popular comedy or children cartoon TV shows, like The Simpsons or Mickey Mouse, where characters act violently, kill each other, or otherwise behave in alarming ways.[3] Well-known creepypasta of this kind includes Slender Man, Jeff the Killer, Candle Cove, The Expressionless, The Grifter, The Russian Sleep Experiment, Smile Dog, Penpal, Polybius, Squidward’s Suicide, or This Man. Another type of creepypasta consists of rumors and accounts of “bad encounters”[4] with computers and the Internet, like cursed data files, haunted CDs, floppy discs or videogames, mysterious websites, or the horrors of the dark web.

The word “creepypasta” has a slapstick ring to it that does not agree, at least on the surface, with the horror genre. Indeed, a quick Google image search returns dozens of comical images of spaghetti Bolognese with “bloody” tomato sauce, and meat or mozzarella balls posed as eye globes. One DeviantArt user even took a charming photograph of a tentacled figure made of wrapped spaghetti strands in a small plate of red sauce, which has been reused in several Internet memes. [Figure 1] A description accompanying the picture states that “I've been told that there’s some sort of image in the spaghetti if you squint your eyes and look sideways, but I think that's a load of hooey”[5]—a comical allusion to urban myths often hitting at concealed images or texts visible only in specific conditions. But not only does this wobbly Cthulhu lack in vitality, with the “creepypasta”’s silly spaghetti tentacles floating listlessly on the sides, but the dish arrangement resembles a cheap mid-week meal, as well as the childish table manners of one who plays with their food. There is a ridiculous contrast between the grotesque grandeur to which the creature seemingly aspires and the prosaicness of the situation. This wannabe eldritch abomination looks rather cute.

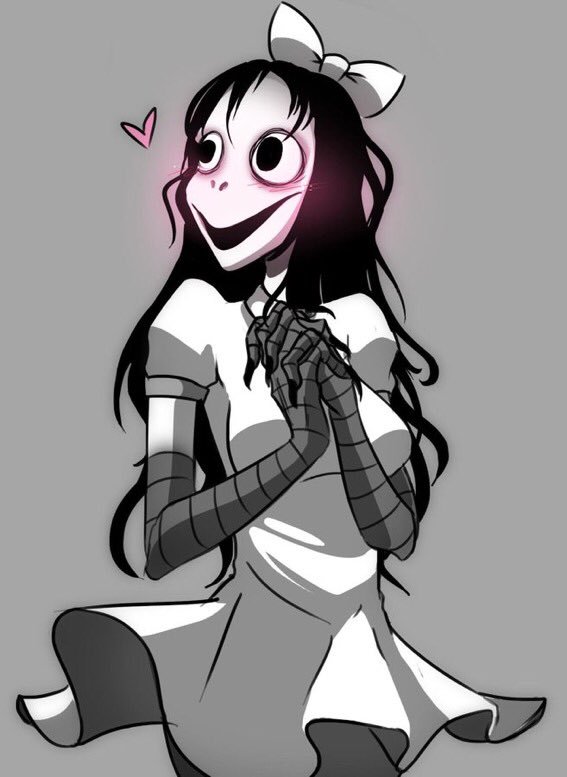

The spaghetti Cthulhu illustrates an interplay of cuteness and disgust underlying various instances of the creepypasta phenomenon. The word “creepypasta” entails a certain degree of failing and diminutiveness, in tension with its horror-themed tales. To some extent, the word “creepypasta” may be meant to declaw these stories whose over‑circulation makes them unreliable and annoying, prompting the contempt (or sometimes, the disgust) of cybernauts. Moreover, many of the art produced by fans about creepypasta is in the style of manga and anime, with characters such as Jeff the Killer, Jason the Toymaker, Candy Pop, Laughing Jake, or The Puppeteer becoming fan favorites in online art communities like DeviantArt. [Figure 2] The dissonance between these characters’ inherent creepiness and their potential to crossover to cute imaginaries is also present in more recent entries to the creepypasta bestiary, e.g., the Momo online phenomenon, which first surfaced in 2016 and later again, in early 2019. [Figure 3] According to Know Your Meme,

“Momo is a nickname given to a sculpture of a young woman with long black hair, large bulging eyes, a wide smile and bird legs. Pictures of the sculpture are associated with an urban legend involving a WhatsApp phone number that messages disturbing photographs to those that attempt to contact it, linked to a game referred to as the Momo Challenge or Momo Game. Similar to the Blue Whale Challenge, many have accused the suicide game of being a hoax.”

In reality, Momo was a statue by Tokyo-based artist Aiso Keisuke, whose work (mainly, horror props for television and film) is informed by his love of yōkai spirits from Japanese folklore; Momo, in particular, was inspired by the ubume, a ghost of a woman who died at childbirth.[7] Although Momo is disturbing, there is an underlying element of burlesque cuteness to her image, her big round eyes and small nose giving her a youthful look, fitting of her name (“Momo” not only sounds cute, but means “peach” in Japanese). So much so that, after the initial panic, Momo became a favorite character in Tumblr and DeviantArt fandoms, and even made the cover of New York’s Buzzfeed newspaper on March 2019, with the headline stating: “How Momo Went from Viral Hoax to Viral Hottie.” According to writer Katie Notopoulos, “Momo has gone from nightmare to dreamy, in record time,” alluding to Momo’s fandomization and the plenty of Internet fanart in which Momo appears as a lovable monster girl, often depicted in anime style. [Figure 4] Additionally, several image macros and fanart emerged on social media in which positive motivational phrases replaced the self-harm instructions that Momo allegedly spread on WhatsApp and YouTube. “Eat healthy. Get exercise,” “You are loved,” or “Believe in yourself”[8] thus became the new maxims of Wholesome Momo, rehabilitated by her Internet fans as an icon of positivity. [Figure 5]

Such linguistic and stylistic features make the creepypasta phenomenon representative of Internet artifacts infused with negative energies—either associated with the horror genre or otherwise deemed harmful to one’s digital hygiene—but rendered in cute visuals or otherwise cutified by online fandoms. Another instance of this is the trend of moé anthropomorphism (moé gijinka), responsible for the fandomization of an entire lineage of hazardous Internet memes. Ebola-chan and Winter-chan are two such cases, to which I now turn.

Both Ebola-chan and Winter-chan are anthropomorphizations of humanitarian disasters as cute anime girls, created in response to the Ebola and Migrant crisis, respectively.[9] As described in KnowYourMeme, Ebola-chan is “a young female anime character wearing a nurse outfit, holding a bloody skull and wearing a ponytail hairstyle ending in strains of the Ebola virus.”[10] [Figure 6] The character, which was initially called Ebola-tan, was created in early Agust of 2014 by a user on Pixiv (a Japanese online art community akin to DeviantArt) immediately migrated to a thread posted to 4chan’s /a/ (anime) board.[11] There, Ebola-chan spread as a reasonably harmless joke through fan art and image macros that, in the fashion of chain emails, urged users to answer with the phrase “I love you Ebola-chan” to avoid contracting the disease. Later, Ebola-chan became more markedly racist, falling victim to the racially-divisive propaganda typical in Internet troll culture.[12]

In turn, Winter-chan, who resembles the protagonist Elsa from Disney’s Frozen (2013), was overtly racist from the start: the idea being that “The harsh, cold winter summoned by the Winter-chan would be painful, or fatal, to those fleeing the Middle East in the European Migrant Crisis.”[13] [Figure 7] Other targets of this kind of toxic moé anthropomorphization include phenomena as diverse as serial killers (Nevada-Tan), deadly diseases (Malaria‑senpai, Marburg‑nee-san, Black Plague‑sama, AIDS‑kun, Rabies‑tan), terrorist groups (ISIS-chan), and government‑developed Internet censorship filters (Ipo‑chan, Green Dam Girl), among others. [Figures 8 & 9] All these characters have Japanese suffixes attached to their names. “-Chan” is the prevailing one, an endearing suffix for a familiar person, usually girlfriends and children, along with “-tan,” a cuter version of “-chan,” as if mispronounced by a child. Other suffixes include “-senpai,” “-sama,” “-neesan,” or “-kun.” These suffixes are common in Japanese language, but in this Internet context are meant to enhance the characters’ anime-likeness, namely, as associated with the otaku’s cult of cuteness and moé. As such, these memes attest to the phenomeno-poetic link between the kawaii and the aesthetics of disgust that permeates the Internet, with more or less malicious intentions.

The world of haunted videogames is another facet of this connection. In the Creepypasta Wiki, there is a category dedicated to videogame-themed creepypasta “For all your gaming weirdness.”[14] The category contains two major subsections, for Pokémon and Legend of Zelda creepypasta. Popular Zelda creepypasta, such as BEN Drowned[15] or Majora’s Mask,[16] revolve around haunted cartridges, hacks, bootlegs, and glitches. [Figure 10] Pokémon creepypasta includes, for instance, the Lavender Town Syndrome, a report of a mass hysteria that afflicted children who listened to the Lavender Town theme music in Pokémon Red and Blue, the first Pokémon game released in Japan in 1996.[17] [Figure 11] The Mario and Sonic the Hedgehog franchises are also popular subjects within the creepypasta community. All these classic Japanese videogames feature mascots like Pikachu and other pokémon, Link and Zelda, Mario and Luigi, or Sonic and Tails, whose lovableness plays a vital role in boosting the creepiness of the stories, contrasting with the pluckiness, bubbly colors, and upbeat songs of 8-bit, 16-bit and 32-bit videogames. Incidentally, the reality is not always as far off from legend as one would think. Case in point: the first season of the Pokémon anime in Japan was marked by the “Pokémon Shock” incident, on December 16, 1997, in which 685 viewers were hospitalized due to epileptic seizures induced by one of Pikachu’s flashing attacks.[18] [Video 1] The event also resulted in a four-month hiatus for the Pokémon anime, and several rules came into force regarding visual effects in animation.[19] The “Pokémon Shock,” being a true story, effectively conveys the uncanny poetics of cute characters gone materially “bad,” even if involuntarily.

Another example is the finding of pokémon inside the Fukushima Exclusion Zone and Chernobyl during the peak of the Pokémon Go mania,[20] an augmented reality game released by the American company Niantic in July of 2016, adding to the moral panic following the game’s release. The fact that one could find Japan’s kawaii “pocket monsters” in the “material metaphors for the filthiest places on Earth,”[21] demonstrates the many contradictions arising when cute virtual characters become threats to the physical integrity of players and nonplayers around the world. On the level of symbolic rather than material risks, local authorities have demanded that Niantic deletes Pokéstops and Gyms (i.e., important points within the game hosted in local landmarks, to which players flock) from solemn sites serving as memorials of civilizational horror and death, like the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, the Auschwitz Memorial, the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington D.C., Ground Zero, and cemeteries.[22] [Figure 12] Such instances of extreme physical and moral disgust were moreover complemented by an endless series of smaller, slapstickish traumas. According to various sources, “Players reported falling over potholes, twisting ankles, and even walking into lampposts and other obstacles as they spent their time engrossed in their phones without paying full attention to their surroundings.”[23] There were also reports of players that fell off a 50-feet cliff [24] or slipped and fell into a ditch, breaking several bones.[25]

Apart from causing severe injuries, Pokémon Go was deemed noxious on several other charges, including muggings, traumatic experiences like finding a dead body in the woods while playing the game, job loss, car crashes, marital arguments, dead batteries and phone viruses, sore legs, data charges, trespassing charges, and even parents abandoning their children to catch a pokémon.[26] Massive human mobs were moved around by virtual cuties, for instance, when the appearance of a Vaporeon and a Squirtle resulted in the sudden crowding of New York’s Central Park[27] and the Santa Monica Pier,[28] [Video 2] respectively. In a stroke of Oscar Wildian “life imitates art far more than art imitates life,” the world seemed to have gone mad in ways reminiscent of the denpa (“electromagnetic wave”) tradition in anime, manga, light novels, and visual novels, in which ordinary people are mind-controlled by exterior forces (electromagnetism, hypnosis, demons, etc.) that make them act in unfamiliar, out-of-character ways. Or, in Kristevian terms, Pokémon Go perceptualized—for a time—the abject realization that there is something “impossible within”[29] us, an invisible otherness stemming from the core of our Self, stealing away one’s control over one’s actions and surroundings.

Omari Akil, author of the article “Pokémon GO is a Death Sentence if you are a Black Man,” goes one step further in describing the underlying racial politics of Pokémon Go. He writes:

“When my brain started combining the complexity of being Black in America with the real world proposal of wandering and exploration that is designed into the gameplay of Pokemon GO, there was only one conclusion. I might die if I keep playing. The breakdown is simple: There is a statistically disproportionate chance that someone could call the police to investigate me for walking around in circles in the complex. There is a statistically disproportionate chance that I would be approached by law enforcement with fear or aggression, even when no laws have been broken. There is a statistically disproportionate chance that I will be shot while reaching for my identification that I always keep in my back right pocket. There is a statistically disproportionate chance that more shots will be fired and I will be dead before any medical assistance is available.”

According to Akil, because Pokémon Go is a location-based video game, it can make players acutely aware that the public space is not equal for everyone. To be fair, there are many redeeming stories about Pokémon Go, like a couple who met while hunting for Lapras (a water-type pokémon) and eventually got married,[31] or the game’s healing effects on folks with mental health issues,[32] including hikikomori shut-ins,[33] or those struggling with obesity or lack of physical activity.[34] Still, Akil’s racialized take on Pokémon Go shows how cuteness and aggression go hand in hand in our real and virtual worlds, highlighting their many gaps and biases. In the end, despite the positive effects of active videogames, excessive gaming is still bad for one’s health, with muscle pains, seizures, obesity, aggressive behavior, poor grades, sleep deprivation, and attention disorders as a few of its costs. On the other hand, computers continue to be associated with many scary, impalpable techno-things that threaten to leak into real life. Like the troll, a creature from Scandinavian folklore which has become a symbol of the Internet’s dark underbelly, of the impulse to crush and wreak havoc, where nothing is too offensive or inflammatory that it cannot be exploited for the sake of “lulz.”

But when creepiness and cuteness are entangled, it significantly alters the phenomeno-poetics of these artifacts and phenomena. They become something else—a dark cute digital aesthetic. It is no wonder that one of the creepiest websites on the Internet, Gurochan, is filled with kawaii imagery. Gurochan is a website where users upload pornographic drawings depicting extreme forms of sexual violence, mutilation, necrophilia, and scatology,[35] most of them drawn in animanga style, often with lolicon themes. [Figure 13] Although the term “guro” derives from the Japanese interwar art movement ero guro nansensu (“erotic grotesque nonsense”), much contemporary guro does not hold the countercultural artistry that makes the former the target of academic interest (certainly, not Gurochan).[36] Existing as an .onion website as well as a regular one, Gurochan has disappeared more than a few times in recorded history. As one Redditor points out:

“The Gurochan system is a patchwork of soft- and hard-wares which do not quite form the coherent system one might imagine. The people it relies on to keep running live scattered all over this gore-spattered planet, and have lives (or so they say). And when you think about it, guro is death and mutilation, so being fragmented and going down all the time, is pretty much in Gurochan’s nature.””

Gurochan’s material scattering echoes the destruction inflicted on the characters, the cute animanga boys and girls made to burst from their limits, crushed and reduced to ruined things. The websites particularly unstable nature has prompted the satirical website Encyclopædia Dramatica to call it “the thing that just won’t die,” stating that “just like any cockroach, it seems that no matter how many times you kill this site, it keeps coming back.”[38] Their description of Gurochan’s current administrators enclaved and ryonaloli suggests that they are insane serial killers and pedophiles and that the FBI monitors Gurochan’s IRC channel. Gurochan may provide a glimpse into what Fred Botting calls “dark materialism,” which “engages matter at the thresholds of its annihilation and disappearance.”[39] Gurochan is always on the brink of vanishing from the Internet, of self-negation, of falling to bits and pieces as its networks collapse and the workarounds fail.

If we accept philosopher Aurel Kolnai’s claim that “disgust is never related to inorganic or non-biological matter,[40] then the repulsion elicited by our digital culture can only be attributed to its non-technologic performance or its filthiness.[41] Therefore, if cuteness is a kind of evolutionary “technology” in and of itself—to ensure the survival of babies and cubs, or facilitate social relationships—one may understand the spread of cute aggressions in our mediaspheres as the result of cuteness that “has started behaving non‑technically.”[42] Indeed, Dylan Wittkower suggests that the predominance of cuteness in digital culture today is connected to the rising popularity of other aesthetics of excess, all sharing a certain degree of emotional immediacy. “The general movement towards extreme images may play a role in increasing the expectation in new media communications for immediately engaging and evocative content,” Wittkower writes. “And so, even though the cute is very different from the hot, shocking, or disgusting, all may play a role in determining the speed and level of desublimation within new media culture.”[43]

Wittkower’s categories of aesthetic excess each in their own way outline what one may call a dark digitality of technical matters, both physical and moral, ranging from general morbidity to the proliferation of online pornography, from resource depletion to digital pollution like bugs, viruses, worms, spam, pop-up ads, clickbait, or Internet trolls. Interestingly, if dark digitality accounts for those undesired remainders of cybercapitalism—supposedly smooth and clean but rotten to the core—these abject human desires are less the turf of “cleaner” official products of corporations than a product of the social media and the boom of user-generated content in the twenty-first century Web 2.0. In sum, Creepypasta, along with related phenomena examined in this section, including toxic moé mascots, Pokémon Go hysteria, or Gurochan pornography, index the interlacing of cuteness and dark digitality on the Internet and in our personal computers, as cuteness, distorted by cybercapitalism, becomes irredeemably laced with digital disgust.

See in CUTENCYCLOPEDIA – (Betamale), Ika-Tako Virus & Red Toad Tumblr Post.

See in PORTFOLIO – Ita-Bag.

REFERENCES in “Creepypasta"

CONTENT NOTICE

This entry is potentially disturbing or unsuited for some readers.Mentions or depictions of abuse, blood, death, excessive or gratuitous violence, mental illness, pornography, pregnancy/childbirth, racism, self-harm, sexual assault, and suicide.Figure 1 Creepypasta by DeviantArt user Melaphyre. Source.

Figure 2 Creepypasta 00 by DeviantArt user seaweed057. Top row: Jane the killer, Homicidal Liu, Jeff the killer, Ben drowned, Lost Silver, Eyeless Jack. Second row: Ticci Toby, Masky, Hoodie, Kate the Chaser, the Seer, Lily. Third row: Clockwork, Suicide Sadie, Kagekao, Lulu, Sally, Lazari. Bottom row: Pinkamena, Suicide Mouse, Max0004, Judge Angels, Bloody Painter and Puppeteer. Source.

Figure 3 One of Momo’s viral photographs. Source.

Figure 4 Fanart of Momo as a cute anime girl. Source.

Figure 5 Wholesome Momo fanart. Source.

Figure 6 Image macro of Ebola-chan that circulated in 4chan in 2014. Source.

Figure 7 Image macro of the racist meme Winter-chan that circulated in 4chan in 2015. Source.

Figure 8 Animated GIF of ISIS-chan, originated in 2chan. Source.

Figure 9 Figure 9 (center) Ipo-chan, a moé anthropomorphized character for the Indonesian web filtering service Internet Positif, originated in Facebook in July 2015. Source.

Figure 10 Figure 10 (right) Illustration for the BEN Drowned creepypasta by Alex Hall. BEN is dressed as Link, the protagonist of the Legend of Zelda videogame series. Source.

Figure 11 Lavender Town in Pokémon Red and Green, developed by Game Freak and published by Nintendo for the Game Boy, 1996. Source.

Video 1. TThe Pokémon Shock scene, from the episode Senshi Porygon. Pikachu uses a Thunderbolt attack, causing an explosion that emits a fast flashing blue and red light. Source.

Figure 12 Illustration of Pokémon Go in the Auschwitz concentration camp. Source.

Video 2 HHundreds of people gathering in Central Park to catch a Vaporeon (a rare pokémon) during the peak of the Pokémon Go craze, on July 15, 2016. Source.

Figure 13 A typical drawing found on Gurochan (censored), by veiled616, 2015. Source.

ABSOLUTE BOYFRIEND ; (BETAMALE) ; BLINGEE ; CGDCT ; CREEPYPASTA ; DARK WEB BAKE SALE ; END, THE ; FAIRIES ; FLOATING DAKIMAKURA ; GAIJIN MANGAKA ; GAKKOGURASHI ; GESAMPTCUTEWERK; GRIMES, NOKIA, YOLANDI ; HAMSTER ; HIRO UNIVERSE ; IKA-TAKO VIRUS ; IT GIRL ; METAMORPHOSIS ; NOTHING THAT’S REALLY THERE; PARADOG ; PASTEL TURN ; POISON GIRLS ; POPPY ; RED TOAD TUMBLR POST ; SHE’S NOT YOUR WAIFU, SHE’S AN ELDRITCH ABOMINATION ; ZOMBIEFLAT